If you have muscle soreness, and you’re having trouble treating it, I want to challenge you to rethink a significant aspect of the way you may visualize how your body heals. It’s not magic. I used to think it was, because I hadn’t contemplated the complexity of my body in the past.

When you obtain a “quick injury” like a separated shoulder or sprained ankle, it is different from an “overuse injury” such as the ones long distance runners get in their shins and hips. Both can hurt in the same way, but an overuse injury is a malfunction that took some time to develop, so your body is aware of it and is trying to heal it; it just hasn’t finished the job yet.

A quick injury, as the name suggests, is something that has just happened to you—often by accident. Thus, on a conscious level you are able to react and contribute to the healing process at the same time as the healing protocol has been initiated by your body on a subconscious level.

Overuse injuries are more physiologically complex, and research in the last three years has uncovered some shocking paradox in the way we understand the body’s repair mechanisms. If you have an overuse injury, see a doctor, assess all aspects of how it was attained and what you do on a daily basis that keeps you from finishing the healing process (i.e. lack of rest, poor nutrients).

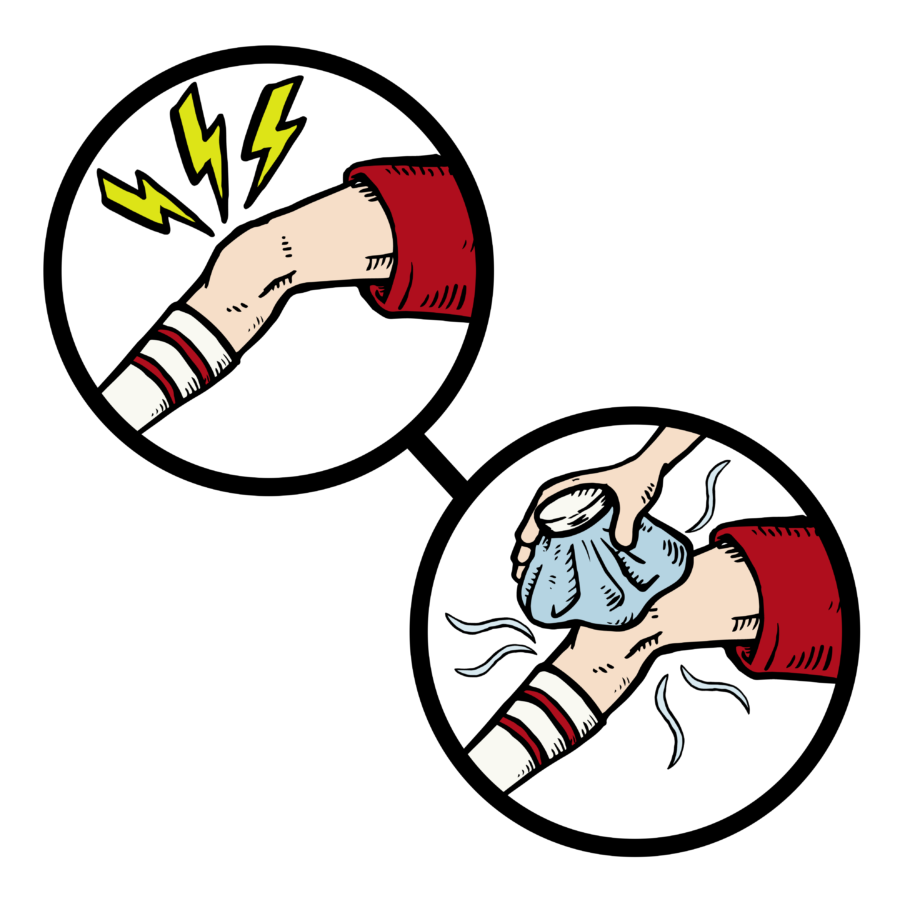

If you have just sprained your ankle, recent studies indicate that indeed, your first course of action should be to ice it.

Icing your tissues shrinks the affected area and reduces inflammation.

One very essential pillar to this technique is the timing: when you apply the ice, and for how long you apply the ice.

With acute injuries or “quick” injuries, ice as soon as possible, but for less time than you’ve been told in the past. Think 5-15 minutes max, then know that ice has done all it can do. The inflammation response you get when your ankle swells is actually a good thing; an evolution on concepts that have been around since the 70’s. Inflammation is the result of your body rushing nutrients and repair-cells to the area, and icing for an extended period of time only serves to slow the enzymatic processes in your cells. This means they do their job more slowly, and they remove wastes slower, and the healing process takes longer. So ice lets the good stuff reach the site of injury more quickly. The healing process begins when blood brings the crucial rebuilding enzymes and proteins. Then the muscles themselves have some work to do.

Later on, use heat. Heat will expand your cells, undoing the very thing you were trying to achieve with icing; but it has an important other effect, heat specifically relaxes muscle cells. It tells them to go into a less active, more recovering state. Thus, cells make better use of the nutrients that made it to them earlier when you were recovering and icing.

Fully repairing any given injury and coming back to full operation and zero pain takes a while. Sometimes we lose track of what helped the body get to that point, In order to manipulate your body to heal faster ice first, heat afterwards. The rule of thumb is heat at night only—when you’re already resting—and only ice new and acute injuries for short, monitored periods of time.