You’re with a couple of classmates in a library study room. You have a political science paper or a math assignment due tomorrow, and three or four of you are working together to power through; amid frequent iPhone fiddling and Facebook checking, somebody says it: “Oh my God, I’m so ADD.”

Indeed, society conditions our generation to multitask and multi-think, juggling a dozen conversations and commitments in the backs of our minds while our schoolwork continues to require greater dedication and focus. To a degree, our society displays more attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder tendencies, especially with the excessive use of technology.

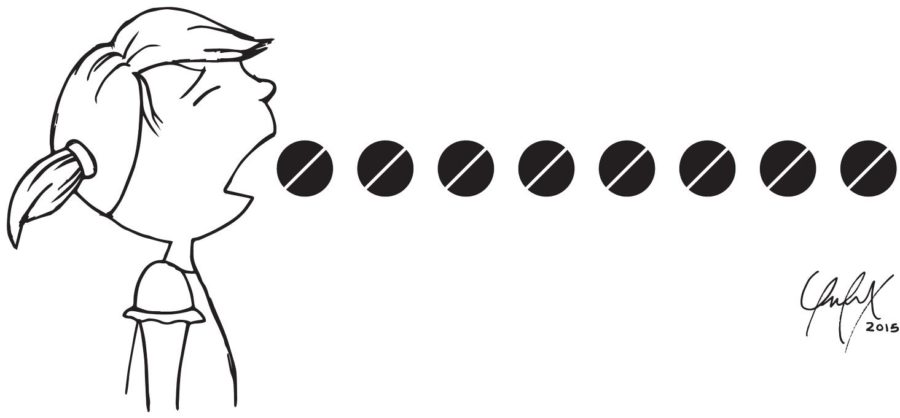

According to the Center for Disease Control, the incidence of bona fide ADD and ADHD in this country is 4-8 percent less than its current prescription rate. In other words, doctors are overprescribing ADD and ADHD.

This means our generation is the product of prescription stimulant experimentation.

One of the most apparent correlations to misdiagnosis of ADD and ADHD is the age range of schoolchildren in a single grade level, and their relative maturity levels.

Because of school age cut-offs, a kindergarten class made up of students who have just turned five, who make the cutoff, and students who are nearly six. At this stage in life, that equates to a nearly 20 percent difference in lifespan.

In a large sample study concerning kindergarteners in a school with a December cut-off, those born in December were 30-40 percent more likely for physicians to diagnose and treat them for ADHD than their peers born at the high end of the cut off.

Even more suspect, girls who researchers averaged into the previous statistic were 70 percent more likely for diagnosis and treatment for ADHD, whereas specialists assumed boys are more hyperactive and less focused on school as a gender stereotype; thus a percentage of boys near the cut-off were not considered to have ADHD symptoms because of gender bias. If a girl the same age was acting excited and distracted, professionals would evaluate her for ADHD due to society’s assumption that girls should be more mature.

This study illustrates that children are often misdiagnosed for a psychological disorder based on shallow criteria: whether or not they can concentrate and complete the same amount of work as peers that almost most 20 percent older.

That’s a significant age difference for doctors to hold a group of children to the same standard.

Len • Oct 14, 2015 at 7:47 am

Interesting…who to believe these days with blogs and opinions galore…. “Doctors Are Getting Most ADHD Diagnoses Right” http://www.healthline.com/health-news/doctors-are-getting-most-adhd-diagnoses-right-101015