By now the story’s so old, it’s probably gone flat – how Coca-Cola shook up ‘Murica with its multilingual version of “America the Beautiful” in a Super Bowl commercial.

But let’s not recycle the same canned counter-reaction here – there’s a Cola War on.

The citizens of the United States of ‘Murica took to Twitter to defend the integrity of their “national anthem” in an outpouring of misinformed, ignorant and racist comments not seen since an Indian-American woman was crowned Miss America in September 2013. Many ‘Muricans expressed they would now drink Pepsi, vowing to boycott Coke for its anti-‘Muricanism.

And why shouldn’t they? Coke has had a distinctly unpatriotic taste, even from its origins as Pemberton’s “French” Wine Coca.

To this day, Coke refuses to include all three of the Star-Spangled Banner’s colors in its logo; any observant ‘Murican keeping tabs on colas can point out Old Glory’s red, white and blue has waved from their Pepsi bottles and cans since the ‘50s.

But the good ole’ boys and girls might want to check their history books.

Much as the Democratic Party began as a party committed to providing a measure of Southern comfort to white plantation owners, but is now better known for trying to choke ‘Muricans with its socialist universal healthcare, Coca-Cola’s initial extraction belies its new polyglottal tendencies.

The “Pemberton” of Pemberton’s French Wine Coca was one John Pemberton, pharmacist, slave-owner and colonel in the Confederate army – a man who could surely identify with the modern ‘Murican movement to make sure everyone speaks ‘Murican in ‘Murica and put a lid on any public acknowledgement of diversity.

Coke seemed well on its way to being the ‘Murican staple, with its formula invented by a Confederate officer and its early corporate officers from good ‘Murican states like Georgia.

One such president, CEO and chairman, J. Paul Austin, was furious when learning Martin Luther King Jr. had won the Nobel Peace prize in 1964.

Furious that King’s accomplishment wouldn’t be celebrated in Atlanta, Georgia – the headquarters of the Coca-Cola Company.

Furious, that the Atlantan elite couldn’t bring themselves to support King with an interracial celebration.

The situation disgusted Austin so much that he called a meeting with Atlanta’s business leaders and told them, “It is embarrassing for Coca-Cola to be located in a city that refuses to honor its Nobel Prize winner.

“We are an international business. The Coca-Cola Co. does not need Atlanta. You all need to decide whether Atlanta needs the Coca-Cola Co.”

The thought of losing their biggest economic associate brought the businessmen around.

Pepsi’s historical actions might confuse its fresh ‘Murican converts in the same way contemporary Republicans might balk at discovering their party’s political beginnings in what are now considered blue states.

Current anti-diversity, ‘Murican cola favorite, Pepsi, also started as the invention of a Southerner: North Carolinian Caleb Bradham. Corporately speaking, Pepsi needed a bit more help breaking through the glass bottle ceiling set by Coca-Cola, going bankrupt twice before hitting on selling 12-ounce bottles at the nickel price of Coke’s 6-ounce bottles during the Great Depression – welfare cola, in the ‘Murican outlook.

In her book, “The Real Pepsi Challenge: How One Pioneering Company Broke Color Barriers in 1940s American Business,” Stephanie Carrell documents how liberal-inclined president Walter Mack started marketing Pepsi to the untapped African-American market in the 1940s. He went so far as to hire actual African-Americans to develop advertisements featuring more actual African-Americans going about their actual daily lives – a further violation of the monochromatic ‘Murican standard, where white skin gets the goods and glory and minorities should keep to their stereotypical corners.

Mack did so well at boosting Pepsi’s sales that he had to hold a meeting to assure his white, largely Southern bottlers that he was “going to have to give Pepsi a little more status, a little more class – in other words, we’re going to have to develop a way whereby it will no longer be known as a n—– drink.”

Also sitting in Mack’s audience was his five-man African-American sales team.

The leader of that team, Edward Boyd, walked out of the meeting in protest. “That was the longest walk of my life,” he said. Support for the African-American-specific ad campaign slowly fizzed out over time.

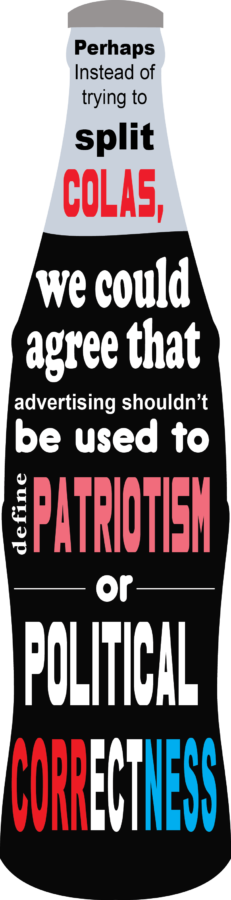

Perhaps instead of trying to split colas, Pepsi for ‘Murica and Coca-Cola for the progressive-minded population, we could agree that advertising shouldn’t be used to define patriotism or political correctness – because just by looking back a ways, it’s easy to put anyone or anything at fault.

From its Confederate roots, Coca-Cola grew a massive globally-driven brand.

Pepsi went from the forward-thinking advertiser to just another racist product of the times, all under one man’s leadership – and yes, continued on to become the giant multinational corporation we know and love today.

Keep angry WASPs out of your soda, but don’t go so far as to think yourself superior to them, either.