We often underestimate the power individuals wield over us and their command over our destinies. For me, as a DACA recipient, my status has been tested by such power and control time and time again.

President Barack Obama established the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program in 2012 to provide immigrants who arrived in the United States when they were young with protection from deportation and a two-year renewable work permit. Through this program, I obtained, for the first time, a shield from the ominous threat of deportation.

Since its inception, DACA has come under legal threat several times, including when President Donald Trump attempted, but failed, to permanently end it in 2017. Its most recent threat occurred in September, when Andrew Hanen, a District Court judge from Texas, ruled DACA unlawful. His decision left the program open for current applicants like myself, but the fates of hundreds of thousands of people hinges on an eventual final verdict from the Supreme Court.

In both situations, as an immigrant and one of nearly 600,000 DACA recipients — colloquially known as “Dreamers” — the control of those in power over my life and destiny has left me feeling numb. While I may be protected from deportation for now, that protection can be snatched away at any moment, and with it, any aspirations I have. Where I live and my ability to legally work and attend school hinges on DACA’s existence. Such an unpredictable legal status has left me trapped in a state of perpetual limbo.

This status has led me to ask myself serious questions: How would I answer questions from authorities if my status reverted back? Would I stay in this country if my family were deported, or would we leave together? Should I confide in others about my status? Should I make my immigrant experience public? Is college worth continuing if my eligibility to work remains in doubt?

Numbness and internal worries lead nowhere. And for every person like myself privileged enough to speak out and benefit from DACA’s protection, millions of other immigrants are not only unprotected from deportation, but may be unwilling to speak out. And for that reason, I’d like to share my story.

Personal Perspective

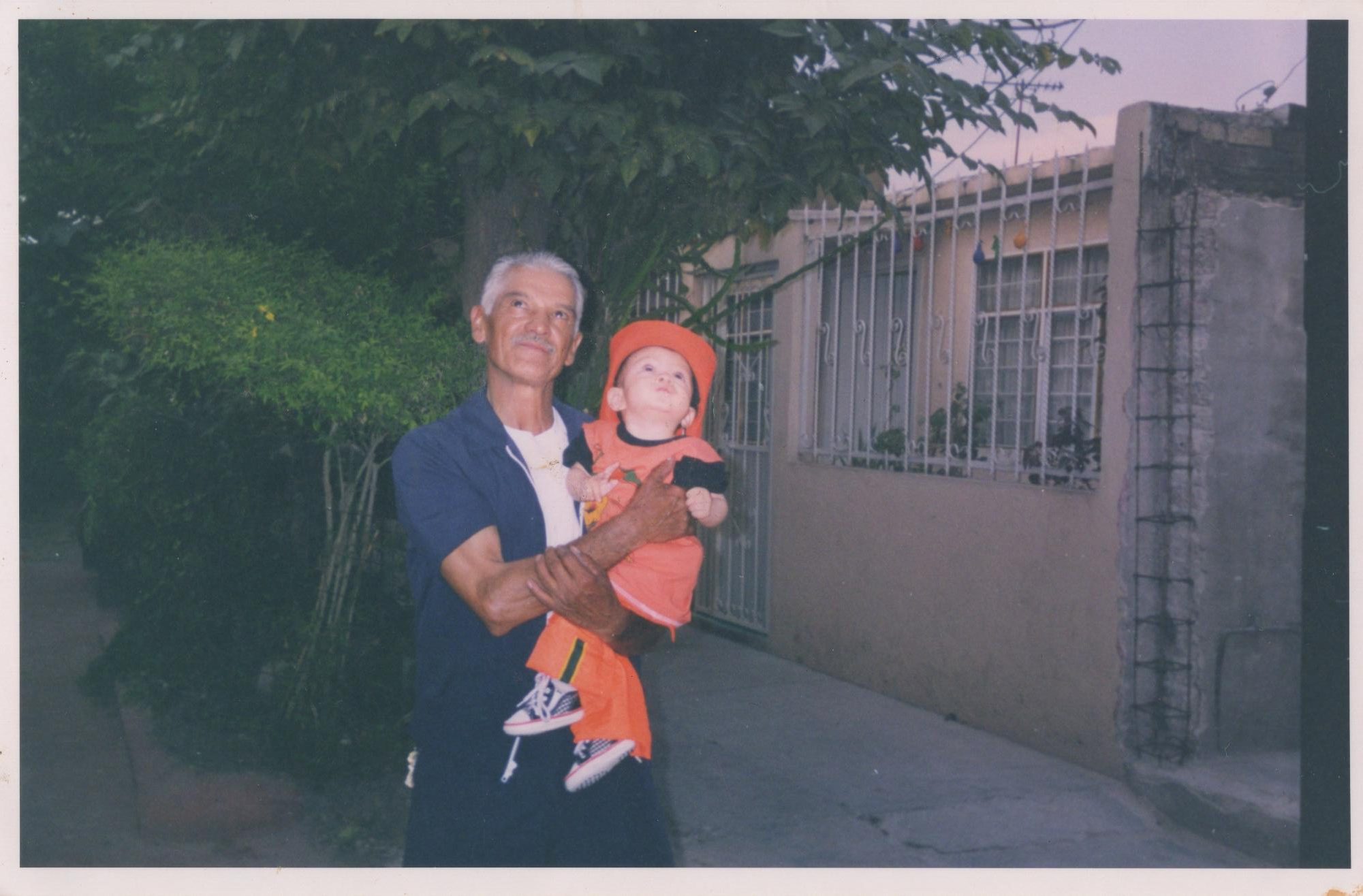

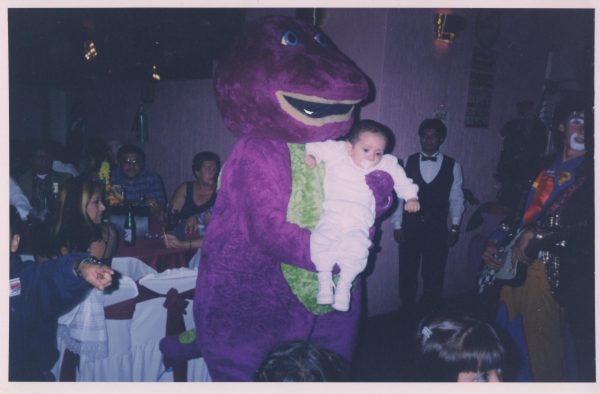

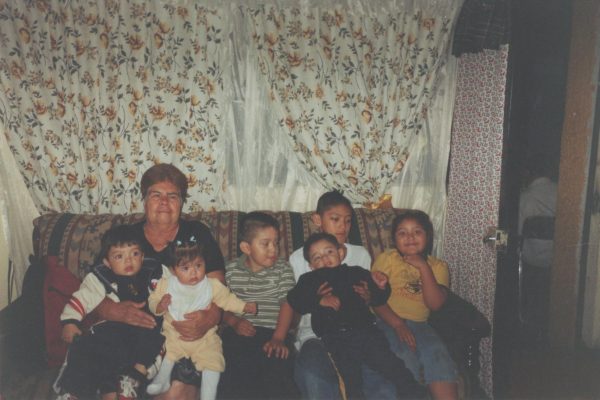

I was born in Mexico City 22 years ago. In my earliest memories, I am surrounded by my extended family — a congregation of cousins, uncles, aunts and grandparents.

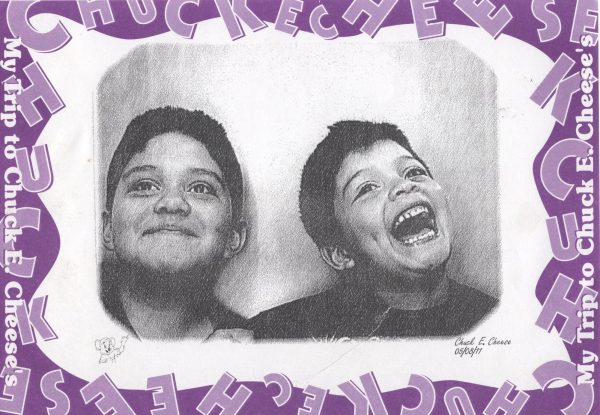

I remember visits to Cancun with my grandparents — my joy at catching a starfish in my bucket at the beach with my cousin, my bravery at petting a baby shark and taking a horseback ride along the beautiful, sandy beaches.

In kindergarten, I was rewarded — or rather bribed — for my academic pursuits with a pet poodle named Pelucha, so I would stop running home from class when my mom dropped me off.

When I was 4, I knelt before a portrait of Jesus Christ my abuelita had in her home, praying for a baby brother. Some time later, I was ecstatic at my parents’ announcement that they were expecting another son.

Within my extended family, I never felt lonely, out-of-place or like I didn’t belong. This radiant aura of welcomeness and sense of community swaddled me and made me feel safe. I remember always feeling protected.

What I don’t remember was saying goodbye.

In search of a better life and education for their two young sons, my parents made the decision — like so many families before us — to immigrate to a new country.

We did not speak the language. We did not know the culture. It was just the four of us together — two parents and their 5-year-old and 1-year-old sons. As much a team as we were a family.

The shift in quality of life for my parents was profound. In Mexico, my mother worked for tax authorities and my father worked in law enforcement; in America, upon arrival, my mother flipped burgers and my father worked as a produce clerk. Gone were the days when we could rely on the family we lived with to help with expenses. My parents’ wages alone had to be enough for us to survive.

Ricocheting from low-paying job to low-paying job, we moved around Sonoma County, living in cramped apartments in Santa Rosa, Healdsburg and Petaluma. Surrounding those ever-shrinking apartments, the vibrancy of local Hispanic Sonoma County communities re-energized the familial connection we longed for.

Cookouts, birthday parties and open-air markets, or tianguis, captured the spark and spirit of Mexico for us. Gazing into the eyes of the friends we made here and listening to the symphony of their laughter felt no different than being among family in Mexico.

As a member of this hospitable community, I thrived. I graduated from Casa Grande High School and then attended Santa Rosa Junior College, where I am pursuing a career in public health as a proud first-generation college student. Most fortunate of all, I was accepted as a DACA recipient.

My success was a blessing. But something often obscured by Dreamers’ success stories is the impact on our parents. Family means the world to my mom and dad, and I’ve been lucky to inherit this trait from them.

But because family means so much to them, it was crushing for my parents to say goodbye to their parents, siblings and cousins in Mexico. For undocumented immigrants in the U.S., leaving home is often a permanent decision; returning to our native country to visit means risking never returning to our home in America. Because of this, our last time face-to-face with family in Mexico was nearly 20 years ago.

What my family lost in being able to look upon the faces of those who they grew up with, they found in phone calls. Calling family in Mexico was a refuge from the pain of not having them at our side.

Sweet and sacred phone calls. Phone calls on our birthdays. Phone calls to say, “Feliz Navidad.” Phone calls to discuss political issues or earthquakes or local news updates. Phone calls that always ended with my grandparents blessing me with a “Que Dios te bendiga.”

These conversations were integral to our sense of family. But because of how far apart we were from each other, deaths of family members stung a thousand times over.

My mom’s dad, my abuelito, died in 2019 after suffering from dementia. My dad’s mom, my abuelita, died in 2021 from health complications.

Both of these losses were crushing, yet my parents rarely cried before my brother and me. Cultural standards prevented them from showing their children excessive emotions, yet their despair was palpable.

My parents’ strength always amazes me. I continue my education because of their sacrifices. Their everlasting endurance inspired me to reach out to individuals not only with expertise on immigration, but who have endured and triumphed.

These individuals included a professor, a community activist and an immigrant service coordinator knowledgeable on immigration and the services and resources available for students at SRJC.

The Advocates

“Every individual should be able to succeed and be given the support to do so,” said Rafael Vazquez Guzman, SRJC humanities & religious studies professor and advisor for Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, MEChA for short. “As a 15-year-old, I migrated to this country due to economic and safety reasons. I want every individual who came here like myself to find the support I didn’t get. Some individuals helped me later, but the isolation and fear I experienced when I first arrived, I do not wish it to anyone.”

Guzman is also the executive director of Líderes del Futuro Avanzando, an immigration services nonprofit organization that helps immigrants and refugees from Latin America with referrals, consultations, travel, status renewals and scholarships.

Líderes del Futuro Avanzando is currently researching the effects of COVID on undocumented students with Dr. Monica Cornejo of Cornell University. Next spring, as part of their “Sanacion y Cultura” advanced parole program, Líderes del Futuro Avanzando plans on traveling with 50 DACA recipients to Mexico to provide tools to cope with the negative effects of being undocumented by focusing on mental health, cultural training and ancestral herb healing.

These projects are among methods Guzman initiated to support immigrants. In the absence of congressional actions to provide DACA recipients with pathways to citizenship, Guzman felt urged to act. “That we often choose to ignore what is in front of us is a choice. I choose to acknowledge it and contribute to the best of my ability,” he said. “As long as you remain in silence, nobody will listen. You must pick up the microphone or the pen and let your emotions out.”

Guzman acknowledges the fear that immigrant students may face, but encourages them to push forward. “Write to your congresspeople. Let them know how you feel about the subject and demand the passage of the Registry Act. You can call or email your representative. Become involved. And if you can, donate to organizations that support this population,” Guzman advised.

Like Guzman, fellow SRJC faculty member Beatriz Camargo also feels a duty to contribute. She is director of student outreach, onboarding and international student programs at the Undocu-Immigrant-Dream Center.

“It’s really been my mission to make sure that everybody can see themselves in a big dream. Even if they don’t achieve that dream, they’re going to go a long way if they’re [reaching toward a] goal,” she said.

Camargo’s SRJC journey began over 20 years ago with her participation in the migrant education program, Adelante, which evolved into working with Mathematics, Engineering, Science Achievement, or MESA, Puente and the High School Equivalency Program, which assists migrant farm workers with obtaining their GEDs. In fact, 10 years ago, Camargo was a founder of HEP.

A self-described “one-stop shop” for undocumented students, the Dream Center provides assistance with DACA renewals, workshops, financial aid and free or low-cost legal support through VIDAS, a non-profit immigrant legal defense organization. It offers HEP graduates a nonresident tuition exemption through California AB540, which allows them to pay the same rate as California residents to attend SRJC.

Despite such programs for students, Camargo acknowledged the challenges undocumented students face.

“It’s easy to feel trapped in this confinement of opportunities,” she said. “But having the confidence to speak with someone that looks like you and telling them your story, it opens up the conversation.”

While proud of the Dream Center’s services, Camargo believes more support is needed.

“It would help to have more staff providing services like visual and in-person support at other sites, where there’s definitely students who are undocumented and need support,” she said.

Despite challenges in staffing for the Dream Center, Camargo remains committed to SRJC students because of her personal connection to the college.

“You know, the JC, it’s like my second home,” she said. “I really feel like it’s got a magic. And I think that it’s not just in its beauty of a campus, and its trees and all the new buildings that are beautiful too, but it’s a lot in the staff.”

Karym Sanchez, SRJC alumnus and North Bay Organizing Project lead organizer, also felt a call to action. Like Camargo and Guzman, Sanchez grew up undocumented.

Sanchez has been involved in community organizing for several years; he was motivated to organize because of the Occupy Wall Street movement, perceived unjust immigrant DUI traffic stops by Santa Rosa Police and the death of Andy Lopez – a local 13-year-old boy who was killed by a Sonoma County sheriff’s deputy in 2013.

In fact, Sanchez knew Lopez well. In 2013, Sanchez worked at Restorative Resources, a nonprofit organization that supported youth at risk of imprisonment or academic expulsion, where he held accountability circles to help adolescents change the trajectory of their lives. Lopez belonged to his accountability circle and was supposed to be with him the day he died.

A sheriff’s deputy shot and killed Lopez as he walked through a park near his Santa Rosa home carrying an Airsoft toy gun he had borrowed from a friend.

Sanchez recalled the moment Lopez’s mom called him on that tragic day.

“‘Mr. Sanchez,” she said, “Andy will not arrive to join the program because he went to his friend’s house, and I think he won’t be able to return because the police closed the street and there’s a man dead in the street.” She did not yet know that it was her own son who had been killed.

Sanchez was outraged at the district attorney’s refusal to prosecute Erick Gelhaus, the deputy who shot Lopez. That decision motivated him to organize high school students to make their voices heard by their community.

Sanchez helped found North Bay Organizing Project as an SRJC MEChA representative, and he would later work to establish the Latinx Student Congress and MEChA chapters across high schools. At NBOP, he is currently involved in advocating for immigrants, tenants, farmworkers and local community members.

“My advice would be to organize, organize, organize. Put pressure on people. Tell your stories publicly. Make people feel uncomfortable with the fact that this is going on,” Sanchez said.

His own immigrant experience taught him the importance of advocating for the rights of undocumented people.

“We have to tell people these stories, if not, they’re just going to remain in the shadows,” he said.

That fight continues for him, particularly in working with undocumented students and DACA recipients. “I think one of the things that DACA students have to remember is that DACA wasn’t won because politicians have good hearts,” he said. “They gave us that because we fucking forced them to. We were holding rallies all the time, and we were holding marches, you know, we were getting organized and pressuring them to give us something.”

Never give up. Continue fighting.

These are the resounding messages I have heard, not just from my parents, but from the advocates fighting for immigrants. Growing up as an immigrant, I felt an obligation to maintain a vow of silence over my legal status, even from my closest friends. But that way of thinking doesn’t bring about the justice and change that millions of immigrants in this country seek and deserve.

We carry the dreams of our ancestors on our shoulders in our struggle. For me, my abuelita and abuelito — who everyday I wish I could still call — are eternally by my side. All their dreams, goals and aspirations live within me. The path forward is through honoring their sacrifices.

A better future is possible, for Dreamers and undocumented immigrants hiding in the shadows. It starts by carrying the torch of hope into the abyss of uncertainty. This hope will remain inextinguishable if we continue to dream and advocate for a better future for ourselves, our loved ones, our community and those who came before us.

That’s the path I intend to take. I hope others will too.