When Janelle Monae sings “Just love me baby, love me for who I am” in her song “Americans,” she’s not asking for the romantic love of any single partner. Instead, Monae is begging for the respect of her fellow man or, more specifically, white men who identify as white nationalists.

It’s not uncommon for musicians to wade into sociopolitical waters when tensions run high.

Musicians have always responded to unjust regimes and advocated for social change. During the ‘30s Woody Guthrie advocated for the rights of field workers. During the ‘60s, John Lee Hooker, Creedence Clearwater Revival and Buffalo Springfield spoke out against America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Thirty years later, N.W.A. protested police violence and mass incarceration, while Public Enemy shed light on issues of drug abuse and gang violence as a part of the black experience.

History has heard musicians resist, and today is no different.

Music is an effective medium for artists to speak truth to power, and musicians from across all genres have been addressing the increase in public hate witnessed since President Trump took office three years ago, in January 2017.

The scourge of white nationalism reared its ugly head again March 15 when a white nationalist murdered 50 people after opening fire in two New Zealand mosques.

The shooter linked his rampage to our president, a man he called a symbol of “renewed white identity.” This echoed the sentiment of many white nationalists who suggest a silent genocide of white values and culture is at work, a genocide that is sacrificing superior values of whites to the inferior values of minorities.

When President Trump was asked that same day whether white nationalism is a growing problem around the world, he said, “I don’t, really. I think it’s a small group of people with very serious problems.”

While the Trump administration may downplay the threat of white nationalist violence, data suggests otherwise.

The Department of Justice’s latest data shows hate crimes increased 17% between 2016 and 2017. The Anti-Defamation League reports the number of white supremacist rallies increased from 76 in 2017 to 91 last year. In a March 2019 article, The Washington Post notes counties that held rallies for Trump in 2016 have witnessed a 226% increase in hate crimes since he was elected.

As these white men get louder in their hatred, so do American musicians in their defiance.

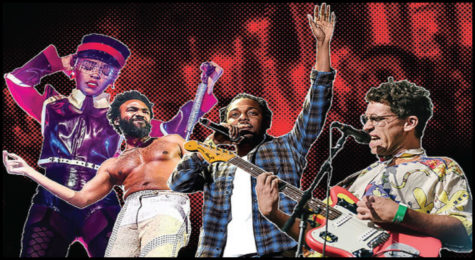

A standout example of music reacting to the current sociopolitical climate is Donald Glover’s “This is America.” Released under his stage name Childish Gambino, “This is America” is an example of one politically charged song which topped the charts last year.

The violence and chaos on display throughout his entrancing music video is juxtaposed with Gambino and a group of black students dancing erratically from one shooting to the next, turning a blind eye to the bloodshed and murder of their own people.

Previously, Gambino never really addressed politics in his music. He started his career as a lighthearted rapper making soulful groovy songs; he never seemed compelled to speak on greater issues. But all that changed when he recorded this track: a song with instrumentals, vocals and visuals that boldly sport an anti-racism message.

Another song that grew in popularity around the issue of racism and the anti-immigration sentiment is Joyner Lucas’ “I’m Not Racist”; it has garnered 115 million views on YouTube since its 2017 release.

Like Glover, Lucas only briefly mentioned politics on past songs, but in light of the country’s increasing racial tensions, he created “I’m Not Racist” to spark discussion on racism.

One half of his song is told through the eyes of a white nationalist who explains why he is resentful of black people and other minorities. The second half is a response to those arguments through the eyes of a black person who is resentful towards white people who have marginalized him and created a stigmatized image of black people.

In an interview with Genius.com, Lucas explained, “This record was definitely meant to make people open up, pause and look at each other and look at ourselves. There is a lot of things that we don’t know about each other.”

The song ends by promising conditions will improve if we understand each other, and Lucas encourages listeners to go outside their comfort zone and reconsider their values.

And the music world’s response to more vocal white nationalists isn’t only coming from black rappers.

The punk band Parquet Courts’ latest album, “Wide Awake,” features social commentary songs including “Violence,” in which the four white band members sing, “Violence is daily life. Violence happens every day.”

In an interview with NPR, Parquet Courts’ singer Andrew Savage explained that while some of their prior work addressed violence, they felt motivated on their most recent album to address the increasing anger in the country.

“Violence is so omnipresent, so integrated in your daily reality, you forget to notice it happens every day,” Savage said. “I also think it was appropriate to honor black artists in a song about American violence, which is disproportionately targeted at black lives. Inherently because of this, it’s also about white privilege and my complicity in the (power) imbalances.”

Then there’s Father John Misty, an indie-folk songwriter whose recent track “Pure Comedy” is a nihilistic take on what he sees as the country’s current “outrage culture.”

In an interview with The New York Times, Misty recounted never being keen on speaking about the political climate, but said he’d grown tired of writing the same old folk songs. He felt compelled to use his voice to address how tumultuous the world around us feels.

On “Pure Comedy” Misty calls out white nationalists as people trapped in a prison of their own beliefs, unable to compromise. He sees them as incapable of understanding anyone with different values or identities. The song ends with a plea for unity: “I hate to say it, but each other’s all we got.”

Even pop music, usually the land of frivolous storylines, has gotten involved. Monae’s “Americans” poses some questions: Why do white nationalists see her skin color before anything else? Why can’t she wield power in society? Why does racism impact every facet of her life from where she can live to how much money she earns?

In an appearance on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” Monae discussed the message behind “Americans” in greater detail. She said people of color “don’t need to be reprogrammed or deprogrammed — we’re fine how we are. We too are American.”

But she acknowledges equality is still not possible. “Until Latinos and Latinas don’t have to run from walls, this is not my America,” she sings. In the song’s spoken word passage, she ruminates on how even the idea of America will never be possible as long as racist white men are in power.

Despite her clear upset at the current state of affairs, Monae ends on a positive note. “But I tell you today that the devil is a liar because it’s gon’ be my America before it’s all over.”

Looking back, we see how this is not just one group of artists or people speaking about this problem. The fact nationalism is starting to be addressed by a range of artists in different genres speaks to the seriousness of this growing problem. While it may be easy to feel hopeless in response to our world, one thing is assured. As nationalist voices continue to shout, the higher musicians will crank the volume in rebellion.