Santa Rosa Junior College’s Multicultural Museum is exhibiting Pomo community-made baskets, the only collection created entirely by Native Americans, for its “Breaking Traditions, Saving Traditions: Elsie Allen and the Legacy of Pomo Basketry” exhibit, which runs through Dec. 22.

This marks the first time the entire collection of 130 baskets, which range from the size of an eraser to 40 inches, has been exhibited since it arrived at SRJC 20 years ago.

The Pomo community are indigenous people from Mendocino, Lake, and Sonoma counties. Pomo weavers are world famous for their baskets.The baskets, created by 26 Pomo weavers, have previously been featured at the Grace Hudson Museum, in Ukiah, and the Mendocino County Museum.

Elsie Allen was the daughter of Annie Burke, who was also known for her basket weaving skills.

It was a Pomo tradition to bury or burn baskets when a person died, but Burke told her daughter to preserve the baskets to teach other people about their culture and tribe. After her mother’s death, Allen wanted to promote the art of basket weaving but had a difficult time trying to find other Pomo women who were interested in it. She believed that basket weaving would lead to making friends from all different cultures and backgrounds.

Members of Elsie Allen’s family spoke about their memories of her at the reception on March 3.

Dan Aguilar, Allen’s grandson, recalled that she collected willows and sorted them on a drying table. The willows took more than a year to dry and expanded once dry. She then used a razor knife to cut these willows.

Susan Billy, Allen’s niece and also a basket weaver, said that her own grandmother had left her basket weaving tools to Allen when she died. Billy tried to take pictures of all the weavers so she could put their pictures next to the baskets they wove in the Grace Hudson Museum exhibit.

“Hearing the personal stories of Annie Burke and Elsie Allen was really special,” said Rachel Minor, museum curator.

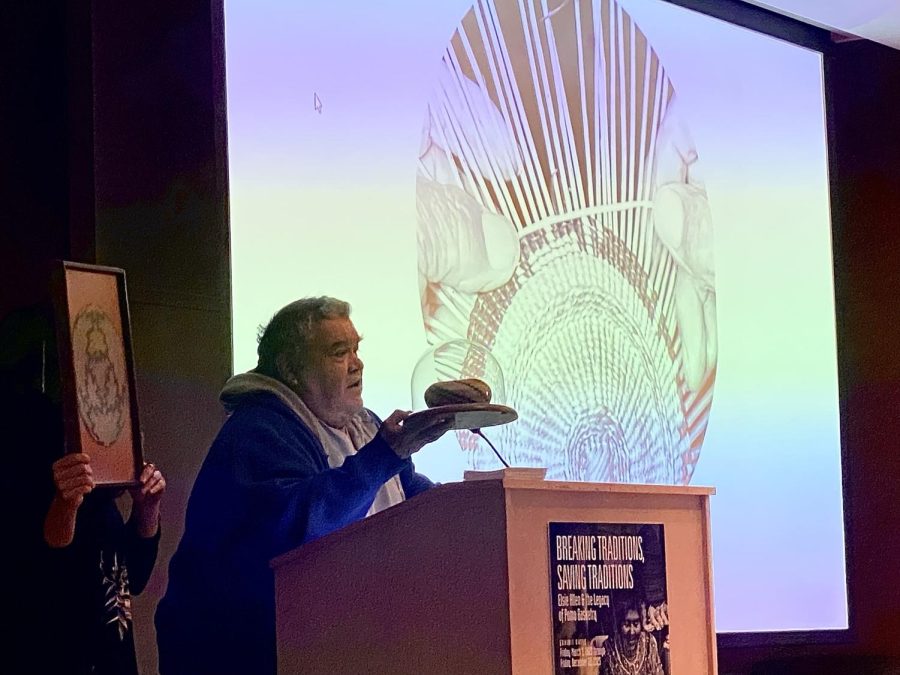

Silver Galleto, founder of the Pomo Weavers Society, started to weave baskets when Allen died in 1990. “Do not honor these women in Women’s History Month, but honor them every single day for what they fought for,” Galleto said.

For a time, he stopped weaving because people told him the baskets he made weren’t as good as the ones his ancestors made. However he resumed weaving because he believed that following tradition is more important than listening to rules.

“Fulfill your dream. We have a new generation of weavers that are committed to revitalizing that which our ancestors attempted to preserve,” he said.

For more information visit the event website or email the multicultural at [email protected]. The event hours are Mondays 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. and Tuesday through Saturday 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.