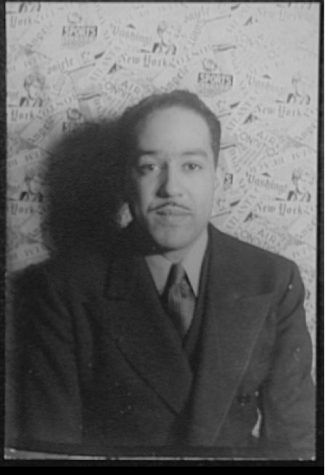

Langston Hughes, the first Black artist to challenge anti-Blackness in America, was celebrated on the 100th anniversary of his first poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” with a discussion of his best works on Feb. 18.

The Library of America, a nonprofit publisher of classic American literature, hosted “The Greatness of Langston Hughes,” a conversation with two scholars, as part of Black History Month over Zoom.

The presentation was sponsored by the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics and Writers, Columbia University’s Center for Jazz Studies, the Hutchins Center at Harvard University, Washington University and the Schomburg Center for Research and Black Culture.

Hughes was known as the poet of the people and pushed against racial boundaries with accurate portrayals of Black life in the early 20th century. He refused to differentiate his experiences from the rest of Black America, which helped drive movements like the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

“One hundred years ago, a short lyric poem ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers,’ appeared in the NAACP Magazine ‘The Crisis, which introduced 19-year-old poet Langston Hughes, who would go on to become a central, indispensable figure in American and world literature,” said Library of America president and publisher Max Rudin.

Hughes was passionate about incorporating subjects like jazz music and Black culture into his art. Unlike many poets of his time, he wrote to a common audience rather than those who explored obscurity. Rudin first discusses the poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Rafia Zafar, professor of African American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis said, “It’s so meaningful in terms of connecting who we are in the United States with our ancestors, people who go all the way back. It’s the quintessential early African American diaspora.”

Professor Brent Hayes Edwards, professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University, marveled at how Hughes wrote the poem in 15 minutes when he was only 18 years old, although it wasn’t published until he was 19.

Edwards said Hughes uses ‘the Negro speaks’ and not ‘I speak.’ This is why Hughes is known as the poet of the people. Edwards said another brilliant maneuver was Hughes’ placement of the transitive verb “to know,” when he uses it to translate the impermanence of a river’s flow.

“You put your hand in a river, and 10 seconds later you put your hand in again and it’s not the same river,” Edwards said. “Knowing a river means knowing flow, and Hughes uses this meaning to connect to genealogy, to lineage and to distance.”

The scholars next discussed the poem “The Weary Blues.”

Edwards argued the poem is about the desire to capture the blues on the page before Hughes experienced the rest of the world.

Hughes was seen as primarily a poet, but Zafar argued his work utilized a collagic effect of music and pieces of music that created literary harmony.

“Hughes was able to literalize music,” Zafar said.

“However, in his earlier poems about jazz, we can tell he’s attracted to the musical aspect of jazz in poetry,” Edwards said. “But he can’t quite get it right, so he dramatizes that attraction from a distance. The poem then takes on that sort of awkwardness.”

Zafar said this awkwardness may be due to the anxiety many creative African Americans had. These individuals often thought music was the truest expression of African-American creativity and other art forms were somehow lacking.

Zafar also suggested “The Weary Blues” was a product of black culture being mediated through white culture.

Next, Edwards recited a lesser-known poem by Hughes, “Johannesburg Mines.”

In the Johannesburg mines

There are 240,000

Native Africans working.

What kind of poem

Would you

Make out of that?

240,000 natives

Working in the

Johannesburg mines.

The poem, written by Hughes in 1925, dares to ask, “Could anything become a poem?”

“The genius is that the question becomes the poem. Nobody had that kind of awareness during the Harlem Renaissance,” Edwards said.

Next, Zafar introduced Hughes’ debut novel, “Not About Laughter,” which confronts the notion of anti-Blackness and how an American coming-of-age novel couldn’t be about a Black boy.

“Whereas others would argue that the poor weren’t capable of a rich life, Hughes was fully aware of the richness that an impoverished life held,” Zafar said.

Zafar sees how Hughes uses this example to fight against these stereotypes.

Publisher Max Rudin read a final poem he believed to encapsulate Hughes’ relevance to society today. “Let America be America Again” was published after the Harlem Renaissance in the ‘30s.

Edwards said the poem reflects Hughes’ internationalist beliefs. It was generally thought African-American writers were on their own, but he was able to connect their struggle to all people.

“Hughes wasn’t just interested in forging those dysphoric connections; he wanted to create a connection between all working people and all human beings,” Zafar said.

Zafar said Hughes wrote this poem to transcend his own generation, making it easier for us to understand structural problems as it occurs in our own society today.

Edwards interprets the poem as a musical, a literary harmony that addresses the perspective of the people rather than the self.

“Hughes uses these marginalized voices and allows them to tell their oppressors that they will win,” Edwards said.

Edwards argued Hughes does not tell readers how to navigate this vision, nor does he pretend it all fits together in one happy community.

“However, Hughes’ allows every man and woman to come together through his poetry, so that they can work towards a peaceful and equal society,” Edwards said.

“He’s not just the poet laureate, not just the poet who represents the people. He is the poet who figures out a way to make the poetry the voices of the people.”