English for Multilingual Speakers (EMLS) instructors and students spoke out for pay equity at the April 8 Board of Trustees meeting.

EMLS instructors have advocated for pay equity with for-credit instructors for more than two years. Their advocacy earned the support of the All Faculty Association (AFA) in 2022, but did not result in changes to their salary.

Former EMLS and current SRJC student Ben Alcantar spoke at the board meeting on behalf of EMLS instructors. He defined the program, formerly called ESL, as “English Saved my Life.” Alcantar started at SRJC later in life. “Without them [EMLS instructors], I wouldn’t be able to move along my path, growing as a person, as a community member, as an employee, as a father, as everything,” he said.

EMLS instructors teaching non-credit courses are paid at a lower rate and required to teach more hours than their for-credit counterparts teaching comparable, or at times, equivalent courses.

Faculty teaching credit courses need to teach 15 hours a week to be considered full time. In contrast, faculty teaching non-credit courses must teach 21.5 hours to be considered full time.

All faculty members are required to serve five service hours and five student contact hours. For faculty teaching for-credit courses and required to teach 15 hours a week, this formula leaves 15 hours of prep time in a 40-hour work week. Non-credit instructors, who teach 6.5 more hours each week, only have 8.5 hours of compensated prep hours.

Daniela Kingwill, EMLS associate faculty, thinks a common perception is that instructors of non-credit courses don’t have to grade as much as instructors in for-credit courses. “But we’re still doing a lot more prep in a different way,” she said. For example, EMLS instructors prepare a lot more scaffolding, such as teaching students how the U.S. college system works and how to navigate the SRJC. “Because our students might be new to the country, newer than credit students, we’re doing a lot of student contact hours,” Kingwill said.

Non-credit EMLS classes provide students with English language instruction to prepare them for taking for-credit courses. The program offers leveled English language learning classes and a pathway for students to earn their associates degree, certificate or to transfer to a four-year college. The program is designed to help people with significant barriers, such as lacking English fluency, landing jobs and starting careers.

English fluency is essential in California, where immigrants compose about one-third of the workforce. In certain types of employment, such as home and lawn care, child care and agriculture, immigrants make up the majority of the state’s workforce. More than one-third of California’s nurses and nearly half of the state’s health aids are immigrants, according to the American Immigration Council.

Alcantar progressed through the EMLS program and transferred into health sciences at SRJC. He will finish his associates degree in fall 2025 and intends to transfer to Sonoma State University in spring 2026 to study sociology and focus on helping vulnerable populations of elders and students.

Alcantar likens EMLS instructors to an assembly line that produces community leaders. “We become leadership of the community,” he said. “There’s so many others that started as I did. They’re already in the workforce, and they’re making the differences.”

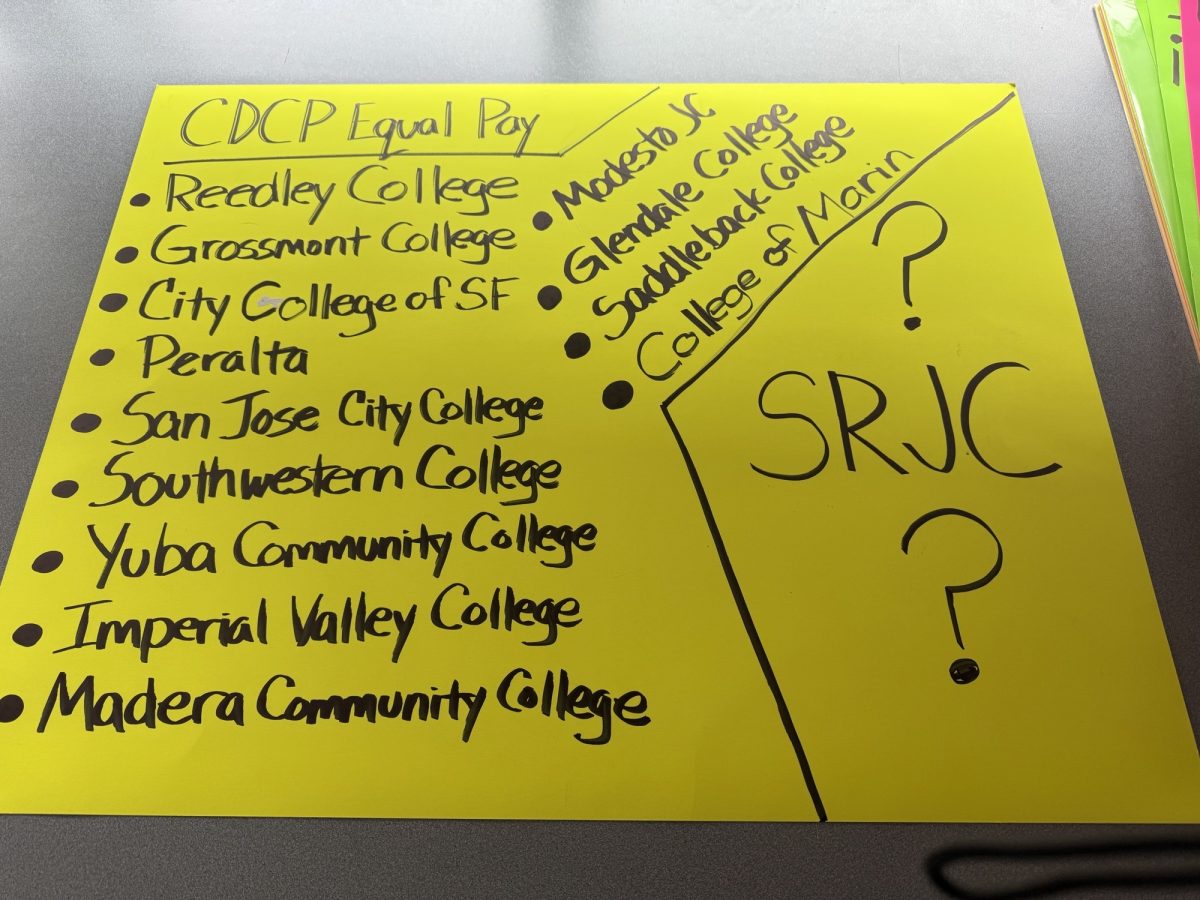

EMLS classes are designated as Career Development College Preparation (CDCP) courses.

“The whole goal of these CDCP courses is to create productive members of our society,” said Daniela Kingwill, EMLS associate faculty. “That’s how the government sees it. … And so if students can get free classes, which then train them to be good workers, that benefits our whole society.”

Kingwill has worked part time for 13.5 years and full time for 8. Because the state funds the CDCP classes at a higher rate than non-credit classes, all EMLS classes, which are considered CDCP classes, are funded at a higher rate. It stands to reason that EMLS instructors should be paid at the same rate as faculty for credit classes, Kingwill and EMLS instructors argue. But that’s not the case.

“Ultimately it would benefit our students if we had pay equity, because if I can dedicate more time to prepping and student contact and fewer hours in the classroom, it will benefit my students in that way,” Kingwill said.

Lesson plans and prep work look different for EMLS faculty teaching to a student population with diverse backgrounds, levels of academic preparation, and levels of language proficiency. The curriculum for language learners includes role playing and navigating real world situations.

In an EMLS course this includes teaching students how to navigate healthcare work opportunities, how to fill out a job application or navigate a job interview, and how to communicate with a boss when there’s a problem, Kingwill said.

Six current EMLS students spoke in support of their instructors at the April board meeting. And five instructors advocated for pay equity. This is the second time EMLS instructors have brought pay equity before the board.

In 2008, Siobhan McGregor, EMLS faculty, undertook a workload study of EMLS instructors. The study determined that a full-time teaching load should be 16.5 hours. At the time, the district-designated full-time teaching load for non-credit classes was 25 hours.

Following the study, the All Faculty Association, the union which represents faculty, negotiated the full-time non-credit teaching load to 21.5 hours, still 6.5 hours more than the full-time credit teaching load.

The discrepancy angered McGregor and other EMLS faculty, who brought up the inequity findings to the Academic Senate in 2022.

In response, the Academic Senate passed a resolution in support of pay equity for EMLS instructors. After it passed, the union initiated negotiations with the district on behalf of EMLS instructors.

“As for negotiations, it’s been a couple of years, and we haven’t heard anything,” said McGregor.

McGregor, who has worked in the EMLS department for about 15 years, has taught credit and non-credit classes.

Now, because credit classes have been paired with non-credit classes, instructors for the credit courses may have more non-credit students in their courses than for-credit students. But they are compensated at a higher rate than their non-credit instructor counterparts teaching the same course.

“Their classes were primarily non credit students, but they were getting paid the contract rate. The rest of us, we’re getting paid less and so I started getting really pissed about this, because it felt very unfair to me,” said McGregor.

Many of these non-credit courses are taught at the Roseland Campus which offers leveled English language classes and language classes for specific types of employment, such as health sciences, child care, culinary and computer.

Meanwhile, the district, along with nearly all California Community Colleges, tries to increase enrollment; it has increased the number of Career Development and College Preparation courses. CDCP courses receive higher apportionment than credit courses.

“We’re a cash cow to that, and they’re using that money to sustain their fund balance, and that’s why they don’t want to give it up and pay us,” McGregor said.

“I just hope we see some movement. One of the things is we understand that maybe we can’t get full pay equity right away. But if they staggered it, that would be a start,” Kingwill said.