As I enter the room in Doyle Library, I hear “tap, tap, tap, clack, clack, clack.” Various spoken phrases fill the space, although no one answers.

The room is full of sound, yet most of the speech is unintended.

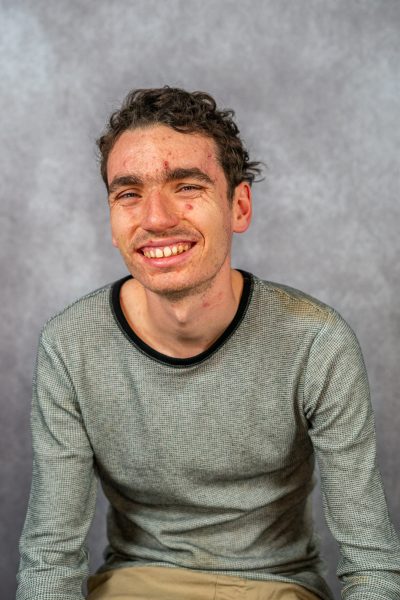

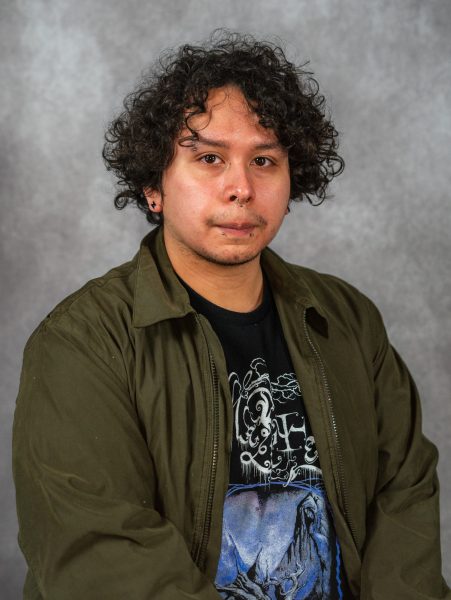

I might say, “Where is my new watch?” Jacob Rochlin spouts important dates. Ryan Heller repeats whatever his communication partner says. Kira Duley sits silently. The iPad’s robotic voice communicates the thoughts that don’t escape our lips.

Our overloaded sensory systems cause a myriad of distractions.

My mind drifts to thoughts of buying new things that clutter up my room and drive my mom crazy. Too many people are talking at once and I cover my ears; the light overhead hums and blocks teacher Lindsey Goodrich’s words. I suddenly stand up from my seat without intention or desire.

Goodrich, 41, leads the discussion for our weekly group meeting. Today we are talking about how to create more fun outings for our little group.

We are a cadre of minimally speaking and nonspeaking autistic students who use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC).

We call ourselves “spellers,” a little-known entity at Santa Rosa Junior College.

We understand everything but might not show it. We prefer different labels, like “minimally speaking” or “unreliably speaking,” but most of us are OK with being called “nonspeakers” since the words we say do not match our thoughts.

We each have a Communication/Regulation Partner (CRP) who helps us focus on using our fingers to spell what we really mean to say. CRPs are also trained to help manage emotional regulation.

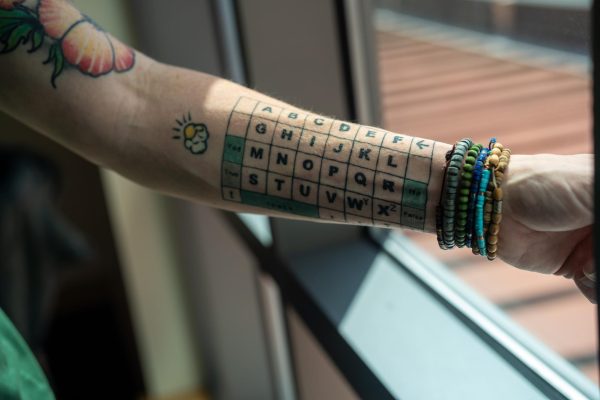

We point painstakingly to one letter at a time on our keyboards or letterboards. A letterboard consists of the alphabet laid out in five rows on laminated cardboard. The keyboards are connected to iPads.

The work is laborious

We are some of the lucky few with access to these communication types. It takes time to learn, money for a teacher and dedicated families who advocate for us. On top of that, finding competent CRPs is a huge hurdle.

Nonspeakers lack funding and access to communication tools.

There are approximately 30 million nonspeaking autistic people worldwide, according to Elizabeth Vosseller, executive director of the International Association for Spelling as Communication (I-ASC).

“One-third of autistic people have significant apraxia affecting their ability to communicate,” she said.

To grasp the concept of apraxia and letterboarding, the general understanding of autism must undergo a significant mindset shift.

According to I-ASC, apraxia is “a neurological difference that affects one’s ability to plan, initiate, execute, adjust and stop motor movements.” Producing speech or reliable speech is a motor function that involves complex pathways from the brain to the mouth. Handwriting is nearly impossible with my poor fine motor coordination.

Vosseller said about 8,000 to 10,000 nonspeakers have access to reliable communication. That’s a drop in the bucket. For every three nonspeakers with access to communication, there are 10,000 without.

There is little to no public funding to learn letterboard methods, so families must find the resources to pay for practitioners. Local practitioners are rare and families often must travel. I learned when I was 14, but my friends Ryan, 26, and Jacob, 22, were in their 20s before they could openly communicate their thoughts, feelings and desires.

Finding my true voice

I dealt with apraxia throughout my life even before I learned the term’s meaning. It involves a brain-body disconnect, which makes purposeful motor actions difficult. For example, sometimes when I want to do homework, I laugh hysterically though nothing is funny. I want to finish my assignment but my body works against me, making the task much harder. When I saw a hot tub the other day, I repeatedly said I’d like to go in. But then I tapped:

I–S-A-Y–T-H-I-N-G-S–I–D-O-N-T–M-E-A-N.

In eighth grade, my family got on a plane to meet a teacher named Soma Mukhopadhyay in Austin, Texas.

The small room contained a table, chair, pencil, paper, letterboard and a tiny woman. Soma looked at my 14-year-old self and knew I was “in there” despite my strange utterances, like answering “yeah” to every question she asked.

Soma asked me to name a word containing the letters A and W. I spelled “A-W-K-W-A-R-D” to my parents’ surprise. And so we went through the alphabet — B and W, C and W, and so on.

“Now, please write a sentence using three of those words,” Mukhopadhyay said. I spelled out my first sentence ever:

T-H-E–L-I-O-N-S–C-L-A-W–L-O-O-K-E-D–A-W-K-W-A-R-D–W-H-E-N–I-T–W-A-S–S-T-U-C-K–B-E-T-W-E-E-N–T-W-O–F-E-N-C-E-S.

Elation! Not only did I have a mind intact, but I was creative. My parents sat open-mouthed. Mom cried. Soma launched me into the world of my intelligent dreams.

At first, it wasn’t easy to coordinate my fingers to reach the letter I had in mind. Excitement and the fear that I might fail to find my true voice slowed my progress. With daily practice, it took me more than two years to effectively communicate with my mom.

Eventually, I felt a huge weight lifted from my shoulders. I could finally say how I wanted my life to unfold. I got my high school diploma doing independent study with my mom as my CRP.

Challenges and allies for nonspeakers

One day in group, Ryan laid down on the floor of the library. We continued our discussion on graffiti artists. He then sprang from the carpet saying, “I want to ask a question!” which really meant he was ready to spell something and needed his CRP. One letter at a time he shared his idea, as if resting helped solidify his thoughts.

The input is there – the output is tricky.

Each week we rotate study rooms, steal chairs from around the library and pile in for our meeting. Jacob makes lists. Ryan asks to go to the bathroom. I smile and wave across the table at Kira’s mom and CRP, Nancy Duley.

Ryan takes roll by typing our names on his iPad. Jacob blurts out calendared events, waiting impatiently for acknowledgment before taking his seat. Kira with her long, red hair sits still. She is the queen of clever quips and cat shirts and our only female member.

The topics vary and we easily digress from current political debacles to playing Trivial Pursuit.

I started at SRJC taking online classes during the pandemic. It was the only option and worked in my favor since I had no CRP other than my mom. No way was I having her attend classes with me.

“Online classes are easier to navigate,” Kira, 22, said. “It’s a challenge to let others know of my abilities when I can’t talk. I want neurotypical people to understand that I am intelligent and just like them. The most difficult thing I encounter is not being able to control my body.”

The truth is I wanted the real college experience as I’d imagined it in my mind for so long. I wanted to fidget at an uncomfortable desk and try to stay awake during a lecture as my attention drifted in and out, competing with persistent daydreams.

Many of my nonspeaking friends were believed to be incapable of learning and not offered effective communication tools during their public school education. Ryan, Kira and Jacob were segregated from their peers and not taught age-appropriate academics.

Having Buckminster Barrett, 30, as my new CRP changed everything. He made it possible to attend class in person. We are still learning together and I can’t say everything I want using my letterboard or keyboard yet, but we make a great team.

“Working with nonspeakers and their families helps me remember what’s important about humanity,” Barrett said. ”You could say it’s beyond words.”

My Journalism 1 instructor, Albert Gregory, changed my perception of myself and what I could contribute to the class. I feel vulnerable when I never know how my anxiety will play out or if I will be able to spell my thoughts in class. Sometimes I preprogram my iPad so I can contribute to the fast-moving discussions.

One day I walked by a classroom next to mine and saw a red ball on the shelf. I was anxious that day. I could not get that red ball out of my mind in class.

My unruly mouth repeated, “I want that red ball!”

Gregory ran out of the room and grabbed it for me. I felt immediate calm, acceptance and gratitude.

“I have learned about what works best [for the student] and tried to accommodate,” Gregory said.

My journalism classmate, Marty Lees, compared my apraxic speech to his grandfather’s lack of speech after his stroke. He described it as a “communication bottleneck.”

“You have this awesome means of overcoming that bottleneck,” Lees said. “It amazes me and makes me proud to be human that such resources and effort have gone into developing the alternative communication methods that you and others use, that you have the drive to use them to further your education, and that people such as Buck are moved to make it their career.”

Two years ago, I was lucky to meet Goodrich, a local assistive technologies specialist who taught me how to use a keyboard.

I switch back and forth each day from letterboard to keyboard, depending on my CRP and my level of anxiety and fatigue. I write these words now by pointing on a letterboard with my mom as my CRP and with Lindsey using my keyboard.

The CRP holds the letterboard or keyboard in my visual field, centered on my pointing finger. My eyes have trouble scanning and tracking. I have not yet mastered the entirely different skill of typing on a flat surface like a laptop. That’s part of apraxia — controlling eye movements. The words I type or spell are always my own.

“As soon as I learned what it meant to presume competence, there was no turning back,” Goodrich said. “I feel that communication is a basic human right, and no matter what it takes, everyone deserves a voice.”

Hard work brings success, acceptance

The Disability Resource Department (DRD) is available for SRJC students with a variety of accommodations.

Disability Specialist Laura Aspinall said, “As of spring 2024, 8.1% of students at SRJC access Disability Resource services.” She was aware of only four students who use AAC.

Accommodations like extended time, the ability to take breaks, the use of fidgets and text-to-speech can help neurodivergent students like me be successful in their studies.

Ryan takes Coding, Kira is in English 1A, Jacob takes Adapted PE and after taking Journalism 1, I am now on staff at The Oak Leaf News. Who would have thought our nonspeaking, quirky crew would become accomplished SRJC college students?

Is it a miracle? No.

It’s the result of years of hard work, dedicated practitioners, CRPs, and families and instructors who believe in us.

Ultimately, our little group is like all young adults wishing for similar things. “I want people to just treat me how you do anyone else,” Jacob said. “I am just human.”

Having a girlfriend is important for Jacob and is something those who speak reliably may take for granted.

“Lately, I’m wishing I can drive myself places and talk privately,” Kira said. “The people who help me are lovely, but I wish I had more independence. It’s a challenge to let others know of my abilities when I can’t talk.”

Having a voice that represents what is in my mind makes my life richer by leaps and bounds. It’s brought me friends and an education I dreamed about for years.

Still, my mind drifts to buying watches to add to the dozens I own. After all, I’m still autistic and love every one of my watches.

“I will tell all willing to listen that not speaking is not easy,” Ryan said. “We all have a fierce drive to be heard and accepted. I hope people will be encouraged to approach us knowing we understand everything. When I am looking with my autistic eyes, there is an intelligent person behind them.”

We all want our intellect in full view for those around us. We are part of the SRJC community.

“Before I could spell, ample language specialists thought my intellect landed somewhere between the mind of a toddler and perhaps a cat,” Kira said. “Then make one little change and believe in me. Suddenly I’m in college.”

Joe • May 23, 2025 at 12:46 pm

Noah I so love reading your work. I am the parent of a 9yo non speaker in public school in Oakland . Next year (4th grade) will be the first year he is included more than half of his day in GenEd, with a 1:1 who we are going to train as a CRP. Lots of work ahead, but we are looking forward to it. Your experiences and that of others informs ours. Thank you.

Gail Ludwig • May 23, 2025 at 11:47 am

Noah, so glad your group is getting recognition and attention. It’s great to see you writing and sharing more. It was nice to you again in person at the spellers’ conference. Adair A.R., Wonderfully article and appreciate the positive research and reporting .

Emily • May 22, 2025 at 10:27 pm

Thanks for sharing your journey. You and your three friends are an inspiration.

Tenaya • May 19, 2025 at 6:55 pm

Another wonderful article Noah! I’ve enjoyed learning about your experience as a Speller, your CRP’s, and your time at SRJC.