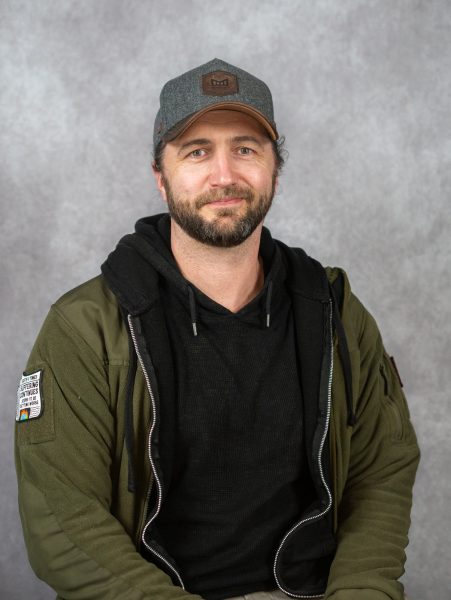

Dependence on technology is a term we hear often in the Silicon Age, but for disabled veteran and Santa Rosa Junior College student Anthony Clark, technology means independence and the ability to stand up for his rights.

The story of Clark’s disability began with a freak accident during Air Force basic training, but the Department of Defense has so far refused to accept Clark’s injury as service-related. Today he is mostly housebound, unable to walk without assistance, and he experiences a multitude of other neurological symptoms. He refuses to let this discourage him in his struggle to get the care and support he feels rightfully entitled to from the country he signed up to serve. AI is giving him the edge he needs to take on this uphill battle.

Physical jobs had always appealed to Clark. Upon graduating from Redwood Academy in Ukiah at 16, he worked in construction with his half brother on highend projects around the Bay Area, including a giant whale installation in Google’s head offices in Mountain View and the entryway to Stanford’s neuroscience center in Palo Alto. But when the financial crisis of 2008 caused the infamous global economic downturn, the construction industry was one of the hardest hit. Clark had to find a new path.

In 2010, then 21-year-old Clark joined the United States Air Force. He was a recruiter’s dream: smart, fit, motivated and willing to be posted to any job that sounded interesting. His father had served decades between the Navy, the Air National Guard and as a sheriff’s deputy for Los Angeles and Oakland counties, so service was in Clark’s blood.

Clark’s chosen career track was to be part of an airborne battle management crew. High above a battle space, on board either an AWACS spy plane — famous for the giant dish on the topside of its fuselage — or an AC-130 gunship — bristling with howitzers, cannons and gatling guns — battle managers coordinate fighters and rain down fire support, surrounded by some of the military’s most sophisticated and secretive technology.

However, during basic training, tragedy intervened to ensure that Clark’s promising career never got off the ground. It was “beast week,” the test of physical fitness and mental toughness at the end of that first training phase before recruits move on to learn their specialist trades. Clark’s squad was running in formation when his foot went into a pothole concealed by the airman in front. He tore his ankle ligaments and fell nine feet into a drainage ditch, landing head-first.

Dazed and in pain, Clark hobbled back to his barracks and agreed with his instructors to tough it out for the last week of basic.

At trade school, due to misdiagnosis of the damage, his ankle never healed properly and brought his Air Force career to an abrupt end, but the bang to his head, ignored by the Air Force medical system, would prove over time to be even more devastating.

Today, at 36, Clark is surrounded by technologies, but they aren’t tools of surveillance and weapons of war. A chairlift helps him get up the steps to his front door, his toilet seat raises and lowers at the push of a button, and Apple’s ubiquitous Siri is always listening for voice commands to turn on lights or unlock the door for visiting guests. All are tasks that would otherwise require Clark to go through the exhausting task of taking his walker 10 feet across the room.

None of this tech comes cheap. It represents just a fraction of the extra cost of living with a disability. Since the Department of Defense doesn’t recognize Clark’s condition as service related, the Department of Veteran Affairs has refused to provide veteran’s disability benefits that could make his life much easier.

The past 15 years have been a constant struggle against worsening symptoms and military bureaucracy. First for a correct diagnosis and adequate treatment, then for recognition. Clark has remained stalwart through it all.

In 2011 at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, though injured and officially awaiting his military discharge, Clark made himself useful to his command by improving the patient tracking systems of the medical hold unit that was now his home.

He helped to streamline the process by which medically unfit airmen could be released to get on with their lives. Still hopeful to heal and get clearance to soldier on, Clark was happy to be useful and was well thought of by his superiors who did what they could to keep him in the service.

All the while Clark underwent excruciating physical therapy on an ankle that was not yet repaired enough to handle the exercises. He began to exhibit symptoms that could not be explained by his ankle injury alone.

“I was having issues with my balance, with numbness and tingling in my lower extremities,” Clark said, “but the only identified, diagnosed issue was the ankle.”

In 2012, still in the medical hold unit more than a year after his initial injury, Clark met physician’s assistant Randy “RJ” Dotts, a former Army Ranger employed in flight medicine at Lackland’s Reid Clinic. Dotts would become a key figure in Clark’s life and the first to recognize what was really going on with his health.

“I always make sure they’re not malingering first,” Dotts said, describing how he surreptitiously followed Clark on a walk and noted that his labored gait didn’t change at all over a half-mile. “He had to use supports to go up a step or stairs, and even had to use supports going down steps, so I knew something was going on.”

Later that year Clark took his accrued leave and moved back to California. His ankle was finally properly diagnosed and rebuilt by an orthopedic surgeon at Los Angeles Air Force Base, yet his other symptoms remained. After the surgery, Clark was discharged from the military around the same time Dotts’ career path took him to a Veterans Affairs hospital in South Carolina.

Dotts advised Clark to come out to South Carolina where Dotts could ensure he got treated by a physician who would give his case the proper attention, and in mid-2013 he did just that. Within six months, owing to his familiarity with Clark’s history, Dotts was assigned as his care provider and continued the investigation. Both Dotts and the orthopedic surgeon who operated on Clark’s ankle agreed the remaining symptoms were unrelated to the damage he had fixed, so Dotts had a rheumatologist examine Clark next. Fibromyalgia was the verdict.

Four years into this nightmare, Clark’s condition was correctly identified for the first time. Chiari malformation refers to the cerebellar tonsils, rounded lobes at the bottom of the brain, slipping into the funnel-like opening at the base of the skull toward the brain stem, impeding the flow of cerebro-spinal fluid. Symptoms vary in nature from physical to psychological and in degree from unnoticed to debilitating.

The majority of Chiari cases are congenital, but, according to professor of neurosurgery, Dr. Judy Huang, more than 25% of patients only discover they have the condition when symptoms begin after some sort of head trauma, such as from a car accident or fall — often after a long, confusing process of eliminating misdiagnoses like migraines, depression or fibromyalgia.

“Symptoms such as headache, or memory problems, or clumsiness are very non-specific, dizziness can be indicative of all sorts of problems… so it’s tough for some people to get to a point where they have a [Chiari] diagnosis made,” Huang said during a 2019 meeting at Johns Hopkins University.

Despite the suggestion from Dotts that Chiari could be the cause of Clark’s deteriorating condition, VA doctors would not look beyond his ankle injury. In mid-2014, on Dotts’ advice, Clark returned to Los Angeles to have his ankle surgeon rule out that injury as a possible cause, hoping that would compel the VA doctors to investigate other options.

Later that year, Clark underwent the first of several MRI scans that showed he indeed had herniation of the tonsillar tissue at the base of his skull. The textbook standard for a Chiari malformation diagnosis is 5 millimeters of protrusion, but that measurement taken from a single MRI doesn’t tell the whole story.

“That number is really just a number,” Huang said. “I can tell you there are lots of people where that number may be not quite 5, maybe marginal at 4 or 3 and they have really, really bad symptoms, and then in other people it can be 10 and they’re not nearly as bad off.”

Clark’s was measured at 3-4 millimeters. A diagnosis is still given at 3 millimeters if it is accompanied by observable symptoms, but the doctors who interpreted Clark’s MRI reported that he was asymptomatic.

Clark is a proud man. He fought against his symptoms to remain independent and presentable for as long as he was physically able. A trained neurosurgeon might have seen through his stoic front, but the doctors who analyzed his MRI were only residents, not experienced enough to look beyond that single measurement — a fact Clark only realized recently when using AI to scour his records for reasons his diagnosis was delayed so many years and why neither an Air Force nor VA neurosurgeon performed a physical examination.

To make matters worse, the judge for Clark’s first appeal for Social Security also fell for his tough guy act and denied his disability claim, insisting Clark was capable of being a vacuum tube operator. “You know, the vacuum tubes they used to have in banks. I don’t know when was the last time anyone even saw a vacuum tube,” Clark said.

Thankfully, Dotts was willing to fly in for the second hearing in 2017 on his own dime to educate the judge on the severity of Clark’s condition, and he was granted 100% disability. “It was the right thing to do,” Dotts said, giving his ranger pedigree credit for his uncompromising sense of duty.

Catching the DoD on to this reality is proving more difficult. It requires scouring reams of information on military law, similar claims made by veterans in the past and Clark’s own data, a task made all the more arduous by his condition.

“I’ve got 4,000 pages, roughly, of medical records,” Clark said. “RJ and I have read through that history at least a dozen times, and every time we’ve always gone back and found something we missed.”

By feeding AI tools like “ChatGPT” from OpenAI and Anthropic’s “Claud” thousands of documents and asking them questions about the contents, Clark, aided by Dotts’ professional knowledge, was able to identify critical points in his records that demonstrate how doctors overlooked his degenerative condition.

“Clear symptoms and objective abnormal findings supporting his [Chiari] diagnoses existed but were not worked up by specialists,” Dotts said. “He should have received a comprehensive workup for his head injury, but this never happened. I was appalled to see how compromised his service treatment records were.”

Dotts didn’t let retirement get in the way of completing the mission alongside Clark. “In 2024, I submitted a service treatment record amendment that documented everything I was instructed not to address while Anthony was on active duty,” Dotts said.

With his medical history corrected, Clark can now use his AI skills to compare his case with the DoD claim records to show where veterans with similar circumstances have been granted the help he needs.

“Anthony will still need to continue his fight for proper recognition, but I can rest easier knowing I’ve finally made his record complete,” Dotts said.

Clark said his case is not the exception, it’s the rule. He hopes that AI can help thousands of other veterans struggling to get the assistance they are due for their service, but he also recognizes that AI isn’t enough on its own. “I pity the veteran who doesn’t have an RJ next to them,” Clark said.

By word of mouth, several other veterans from across the country have reached out and are currently working with Dotts, but he won’t fight their battle for them. “RJ is also very clear. You gotta be in the trenches with him,” Clark said. With AI assistance, their chances of victory are greatly increased.

Rj • May 19, 2025 at 5:46 pm

Public Comment Regarding the Need for In-Depth Examination of Artificial Intelligence in Legal Self-Representation.

I respectfully propose that additional research articles be developed and published by you to thoroughly explore the emerging role of artificial intelligence in legal self-representation.

Such scholarship would provide valuable documentation of Mr. Clark’s significant fifteen-to twenty year journey navigating complex legal and medical challenges without professional representation.

Of particular importance is how artificial intelligence technologies have provided crucial assistance in his pro se federal litigation against the Department of Veterans Affairs regarding allegations of alleged medical malpractice, as well as his ongoing proceedings with the Department of Defense concerning potential disability rating adjustments and associated medical retirement benefits.

This case merits scholarly attention specifically because Mr. Clark, despite diligent efforts to secure legal representation, found that no attorneys were willing to accept his case. This highlights a concerning gap in access to justice where the oft-cited principle of representation “for the people” appears to conflict with economic considerations that govern legal practice.

I express my professional support for individuals who demonstrate the determination to advocate for themselves within our complex legal system, particularly when assisted by emerging technological tools that may help bridge the representation gap.

Sincerely,

Randall James Dotts, PA-C Retired