Food insecurity in Sonoma County: Hunger and action in the land of plenty

Student staffer Daniel Akoue was working the Santa Rosa Junior College Bailey Field food kiosk just after 9:15 on a sunny May morning before opening shop at 9:30 a.m. He hoisted a large cardboard box of red apples onto the tables, alongside the potatoes, onions and heads of lettuce already out. Then he placed milk crates of Oreo Cakesters, organic apple-sauce pouches and varieties of bread, everything from a keto loaf to burger buns to wheat bread, along the front counter in front of the kiosk windows.

He expected to see the usual 50 to 150 people come by that day, he said, including students, staff and community members. Shelves inside the kiosk held boxes of hot and cold cereal, breakfast bars, instant ramen noodles, single-serve cartons of shelf-stable milk and various snacks. A refrigerator inside housed a large box of eggs.

Savanna, a younger student who opted not to provide her last name, said she’s been coming to the kiosk for a couple of semesters. Today she was hoping to find her favorite snack, apple-sauce pouches, along with produce and other staples.

“My family has loved me bringing home cereal, milk, containers of water,” she said, adding that she lives with her mom and dad.

An older student named Deborah, who also asked not to use her last name, has visited the kiosk several times before with her ASL interpreter. “I pick and choose whatever they have here,” she said. This morning, she selected potatoes, lettuce, a cup of noodles and a frozen burrito she’ll use for meals and small fruit packages for snacking.

Student Eddie C., who didn’t give his full last name, stopped by next. The part-time college student and part-time worker, 33, saves on the cost of living by sharing rent on a three-bedroom flat with two other people, and he’s grateful for the food aid on campus. “To have this food available is a huge help,” Eddie said.

After choosing produce, he was surprised to find eggs available: “I’m really glad that they’re giving out eggs today. They’re so expensive,” he said.

Egg prices have surged more than 60% since January 2025, as the nation’s chicken ranchers tried to control the spread of bird flu in their egg-laying flocks. Killing their ailing stock has led to egg shortages in supermarkets.

Full-time marketing student Vannessa Allen, 20, who occasionally visits the kiosk, knows what it’s like to rely on others for food help.

In a phone interview, Allen recalled her mother using government-issued food stamps to pay for groceries during three years of hard times in her childhood. “We didn’t necessarily get what we wanted, but we got the staples,” she said.

Allen has lived with her grandparents since she was 9 and says her folks pay for food at home. Her part-time sales job at a tanning salon covers her other expenses. “So I pay for my phone bill, my car insurance and my gas. And then like sometimes I’ll get fast food just because like that’s easiest for me after work. And then like Starbucks sometimes.”

In June 2025, the U.S. Senate will vote on the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which proposes major cuts to food aid, known as SNAP, short for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that if the budget act passes, adding a work requirement for SNAP recipients will save the federal government $267 billion from 2026 through 2034.

SNAP applicants who could not meet the work requirement would no longer receive this food aid.

Allen said, “That would just be detrimental honestly. Like I said, I got the basics from food stamps. I was able to get milk and frozen foods, bread and stuff like that, and that was really the only way that we were able to get food, so if that would be taken away from some families, I really think that’s detrimental.”

Lily Hunnemeder-Bergfelt, director of re-entry and student resources at SRJC, said the need to provide food aid to students became apparent after the 2017 Tubbs fire and other disasters in the following years. “There was a huge increase in homeless students,” she said. “We were noting that students were always hungry. It became very obvious that students were not able to meet their nutritional needs.”

The California Budget Act of 2023 allocated $43.5 million annually to the state’s 116 community colleges to establish centers that help students take care of basic needs, including food, transportation, housing, and mental health.

In May 2024, the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office reported on these efforts at 80 colleges: “Nearly half of all (68,429) students who accessed Basic Needs Center resources received food security assistance.”

These efforts include facilitating CalFresh applications (state and federal funding specifically for groceries), food pantries, meal vouchers and grocery-store gift cards, among other assistance.

SRJC Student Resource Centers staff help students take care of basic needs so they can focus on their studies and personal growth. Two full-time social workers and a team of support specialists help connect students with funds, food and other aid.

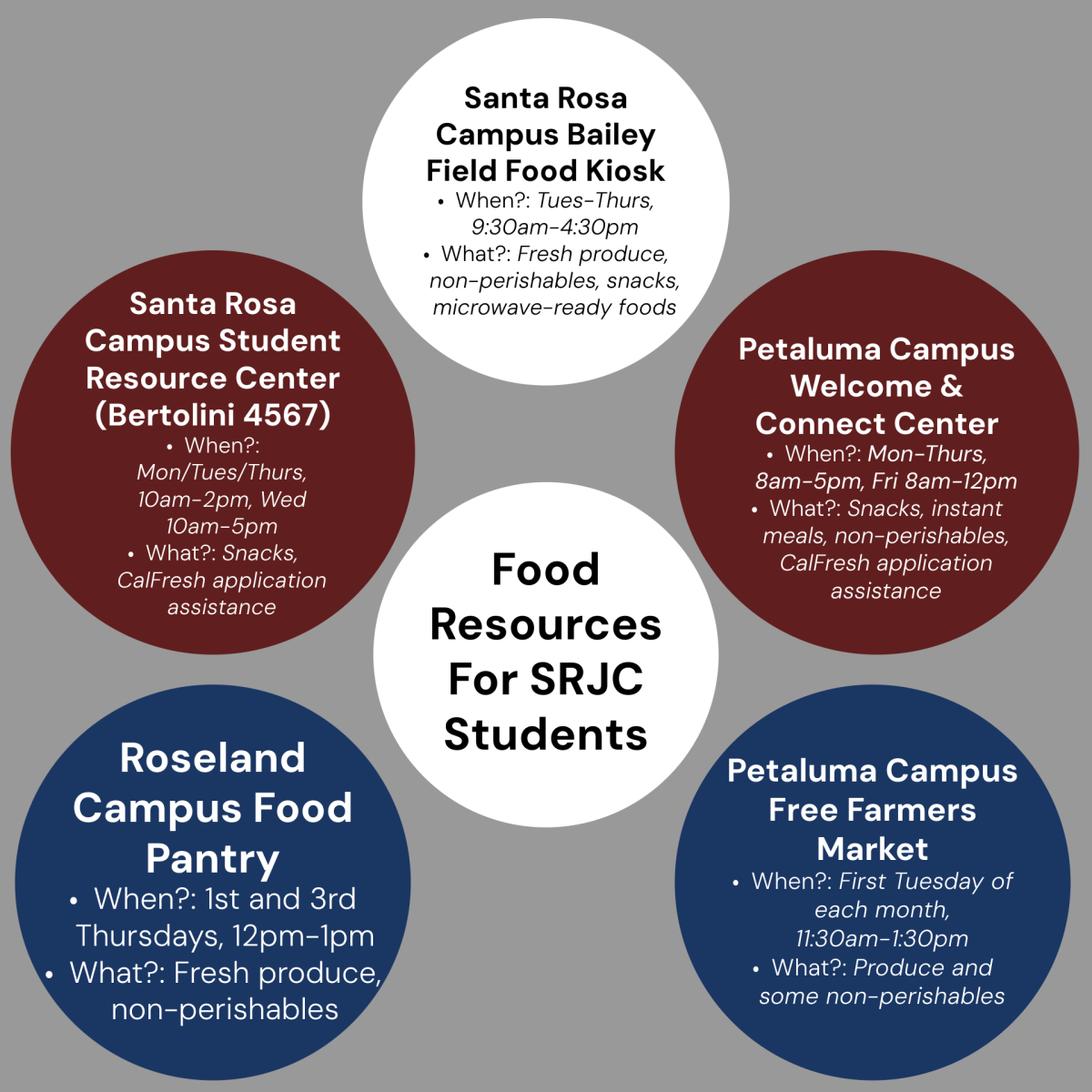

On SRJC’s Santa Rosa campus, the Bailey Field food kiosk is the largest and most visible sign of food assistance, open Tuesday through Thursday from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Hunnemeder-Bergfelt keeps track of the kiosk’s staffing, inventory, ordering and service. In March 2025 alone, kiosk staffers provided food to 458 individuals, some of whom came by several times that month, for a total of 1,592 client visits.

The food assistance program also supplies snacks and quick foods to students at 37 other locations around campus, said Hunnemeder-Bergfelt, including the Bertolini Student Center, the Dream Center, the Doyle Library reference desk and the Lindley Center for STEM Education.

The food comes from various sources: donations and purchases from Redwood Empire Food Bank, produce from Shone Farm and purchases from the food vendor for dining services.

SRJC Petaluma’s food distribution program serves about 200 students over the course of a semester, said Michelle Vidaurri, director of student engagement and support services. Located inside the Welcome & Connect Center, the food pantry is open to students whenever campus is open, even during the summer.

“Food pantry items include healthy snacks, food staples like beans, rice, some vegetables, and nonperishable foods that are a good source of protein, such as shelf-stable milk, soups, tuna or chicken salad kits, and protein drinks,” Vidaurri said.

In addition, the campus has smaller free food kiosks in the tutorial center, Mahoney library, counseling department and student center.

Once a month during the academic year, the Petaluma campus hosts a farmer’s market that’s free to the broader community as well. “We purchase food from Redwood Empire Food Bank: fresh vegetables and fruit, peanut butter, eggs, bread and milk,” she said.

SRJC’s Roseland center on Santa Rosa’s South Wright Road distributes free food to students from noon to 1 p.m. on the first and third Thursdays each month while classes are in session.

Roseland director Héctor Delgado said the center’s food program originally started with a snack pantry, which was open four days a week. Recently, the center has partnered with Redwood Empire Food Bank to provide food to students, delivering about 1,700 pounds of food on the first and third Thursday of the month.

“Students can get nonperishable items such as bread, rice, beans, canned foods, juice as well as produce available from the food bank at that time, sometimes including potatoes, onions, celery, cucumber, carrots, whatever is in stock,” Delgado said.

He hopes to expand services over time as the center’s student population, staff and footprint grow. Delgado said he expects food insecurity and housing to continue as students’ greatest needs in the future.

Prices for food, housing, utilities and transportation rose 2.4% nationwide between March 2024 and March 2025, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. CNBC published a chart that breaks down inflation for food, energy and other living expenses.

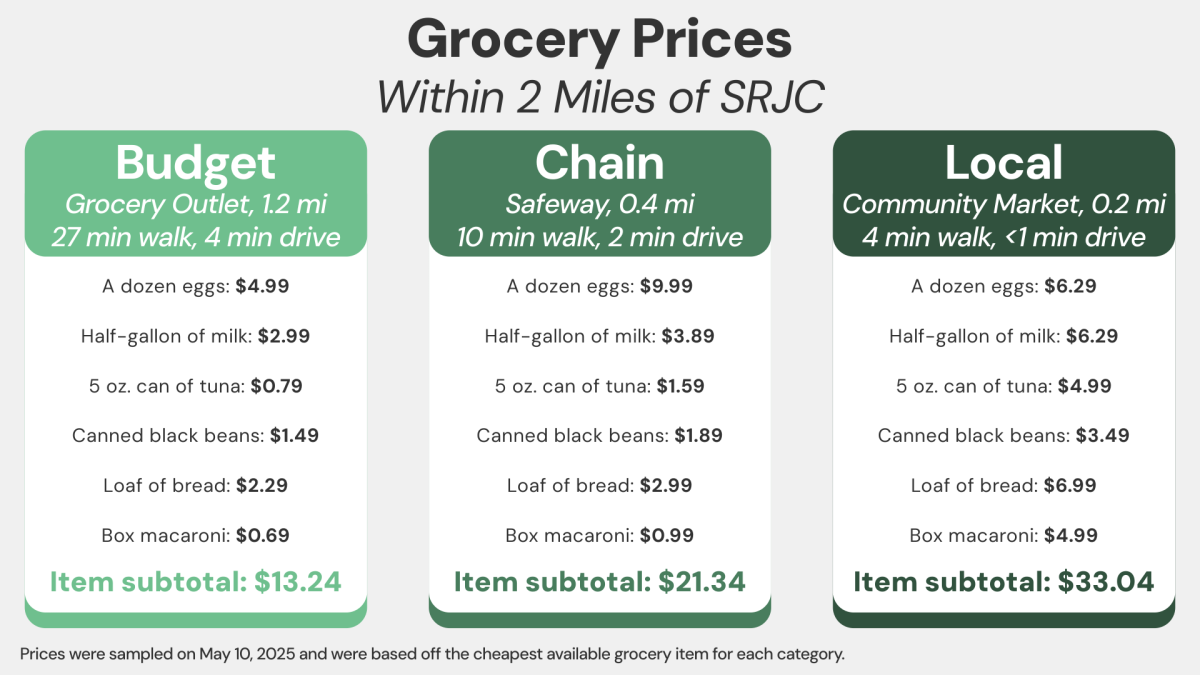

Consumer prices for Sonoma County specifically increased by 2.2% over the year. But the cost of food alone nearly doubled that, by 3.7% in the county, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (see page 2).

Shoppers can see varying prices for food at county supermarkets, but finding variety, quality and bargains takes time and effort. On May 10, a dozen eggs cost $9.99 at Safeway but $4.99 at Grocery Outlet; canned tuna sold for $1.59 at one store but $0.79 at the other; bread was $2.99 at Safeway but $2.29 at Grocery Outlet.

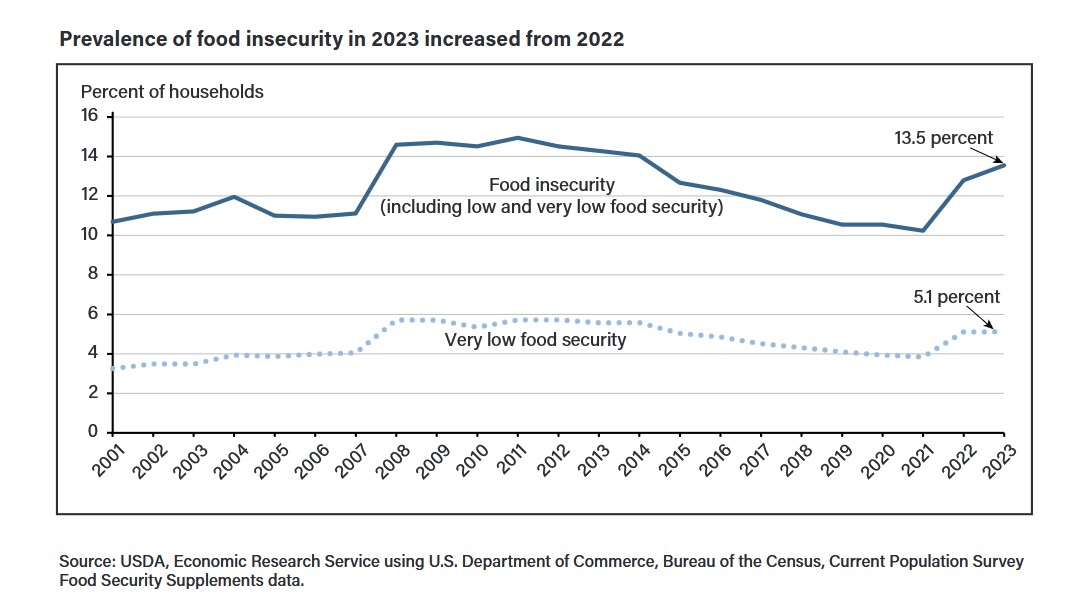

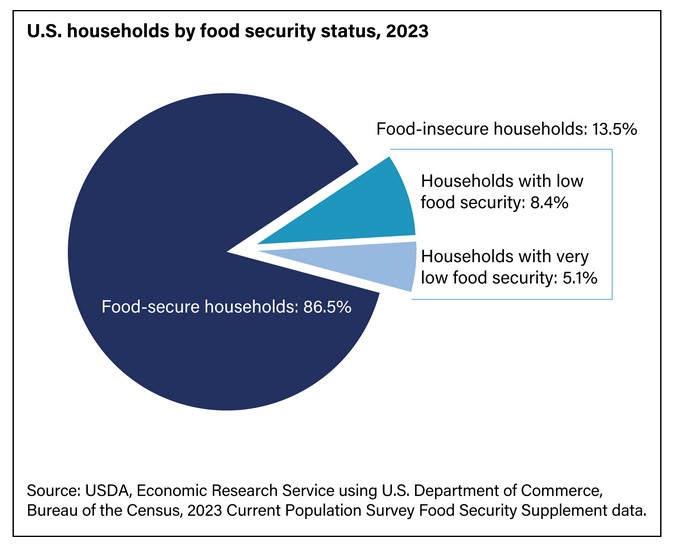

The U.S. Department of Agriculture classified Americans’ access to food in 2023 into two main groups: The food secure had consistent, dependable access to healthy food, and the food insecure lacked the resources to afford enough quantity or variety of food on their own to live active lives. The USDA counted 18 million people, or 13.5% of the population, as food insecure that year.

In a 2019 article using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, which focused on adults ages 24 to 32, researchers showed that those with food insecurity were more likely to have poorer overall health, with conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity and difficulties with breathing — conditions that can become chronic over time.

Rachelle Mesheau, director of marketing and communications for Redwood Empire Food Bank, said support needs for those who are food insecure varies. Some require short-term help, such as while waiting for a paycheck, and others need assistance over a longer term.

“Food is part of what makes a person whole,” said Rosa González, 36, the executive director of the nonprofit gleaning organization Farm to Pantry in Healdsburg. The director, who has a master’s degree in public health, said, “It’s a social determinant of health.”

Her nonprofit’s small staff organizes volunteers to harvest produce, ranging from a single lemon bush to entire orchards, all over the county.

Recently a property owner donated 700 pounds of lemons.

Farm to Pantry also collects food and plant starts from farms such as SRJC’s Shone Farm and local farmers markets, then distributes it to more than 75 partner organizations across the northern county, from senior sites and health centers to community groups.

Because Farm to Pantry counts farmworkers among the people who receive the food it gathers, the group tries to provide culturally relevant foods — such as cilantro, tomatillo, tomatoes, squash and cucumbers — to please both the stomach and the palate.

Farm to Pantry is always looking for volunteers. “When you glean with us, you’re in the most beautiful locations in Sonoma County,” González said. They also need volunteer drivers for pickup and delivery, and they need donors to fund their efforts.

Healdsburg residents Bruce Mentzer and Anthony Solar started their nonprofit, Farm to Fight Hunger, in 2019. Mentzer studied sustainable agriculture at SRJC’s Shone Farm for two years, learning about soil science, crop planning and sustainable farming. He drew up the original plan for their nonprofit as a class assignment, then put it into action.

The farm now contains five acres of crops and about 250 hens. All of its produce and eggs go to food banks and other community organizations — “100% free,” Mentzer said.

“The first year, we grew and donated 4,000 pounds of vegetables on 15 rows, and we’re up to 140 rows now. We hope to grow 100,000 pounds this year.” One week in late April, they donated 150 dozen eggs to the Healdsburg Food Pantry.

Volunteers help Mentzer and Solar’s two paid staff members put in plant starts, tend the crops and harvest the food. Neither founder receives a salary.

Mesheau of Redwood Empire Food Bank said her organization has seen steady growth in people’s need for food support across the five counties it serves, with a yearly increase of 10% since 2017.

In the group’s 2024 Impact Report, Allison Goodwin, president and CEO, explained: “We’ve seen a continued rise in people needing our help, with an average of 3,300 new individuals turning to us each month.”

The food bank served 142,000 people across five counties in 2024, including 112,180 individuals in Sonoma County alone, Mesheau said. Of the $74.5 million in food their staff and volunteers distributed directly, 92% or more than $55 million went to people in Sonoma County. The food bank also supplies food for 150 nonprofit and community organizations to distribute. The food bank’s interactive Get Food page helps hungry visitors find a nearby location to pick up what they need.

“We rely heavily on our community for support,” Mesheau said. She emphasized the community’s generosity: food donations come from markets, farms and individuals; volunteers donate hours of time; federal, state and county governments contribute funding; and grants and individuals supply more funds.

“When you receive support collectively,” she added, “there’s no end to what you can do.”

Delgado of SRJC’s Roseland center said the need for food assistance for students and others is likely to continue into the future. “We live in an area that is very expensive, and given inflation, the cost of food items, the cost of living, cost of housing — I think the demand for help will continue to grow. It’s not going to slow down.”

At the SRJC Bailey kiosk, student Savanna said she’s grateful for the food support: “I just love that it’s able to help so many people. It’s always packed, and they have so many foods. I just learned there’s also food at the Student Resource Center over in Bertolini, and they even have a clothes rack you can look through.”

Friends and SRJC students Jaky, Zaira and Rana, who declined to give their last names, sat nearby on a bench in the sun. Each had picked up a hummus cup and a granola bar at the kiosk.

“Sometimes I miss breakfast when I have an early morning class,” said Jaky, “and I can just come by to get something to snack on.”’