Wine in America: Are the kids drinking enough?

Kate Nowell-Smith, a winemaker and writer for Decanter Magazine, has been enamored with the process of fermentation her entire life.

Her father started fermenting beer in their cellar because he was from England and missed a good British pint. “It was terrible, execrable, you could say, but gave me a love of fermentation from a very early age,” Nowell-Smith said, her Ontario roots coming out in a slight rounding of the vowels while speaking. “Just magic, a smell that was just magic, this transformation through controlled spoilage.”

From those first forays with fermenting ginger beer to culinary school, classes at Santa Rosa Junior College, a winemaking certificate from UC Davis and career as a winemaker and a writer, she has seen the wine industry shift and fluctuate.

Change, and very little of it good in the short term, looks self-evident to the majority of wine professionals. The grape growing and wine making business — a staple of Sonoma County’s culture, economy and self-perception — is changing, bracing for the impacts of uncertain tariff decisions, climate change and a dying core customer base.

It used to be that Sonoma County was apple country, with more than 6,000 hectares planted in the mid-20th century before the vast majority were torn out when grapes began promising success in the 1990s.

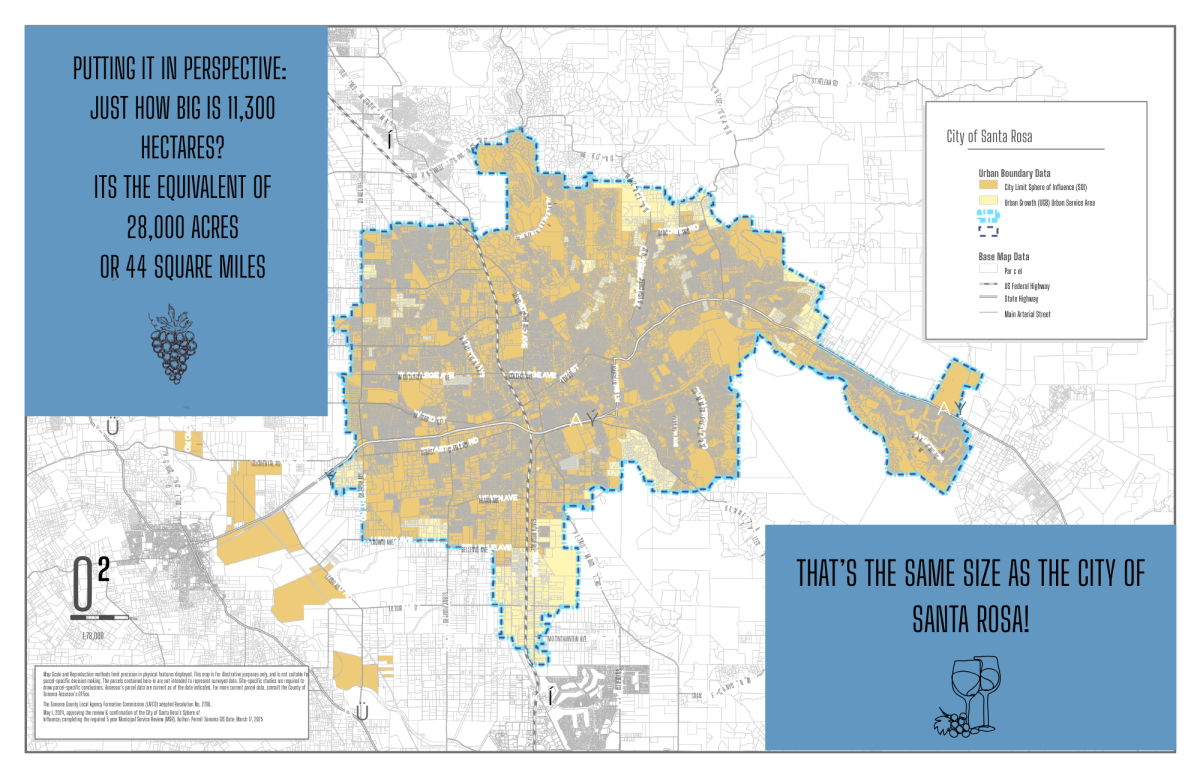

That cycle of boom and bust appears to continue. With some growers associations recommending that 11,300 or more hectares need to be removed to prevent overplanting and the baby boomer generation drinking less wine, experienced winemakers and importers alike are beginning to feel the hurt, Nowell-Smith said.

But beyond that, on the personal and cultural level, she sees these changes as indicative of, and resulting from, social unease and disconnection.

“I really think we are losing community on the macroscale and the microscale. I’m not religious, but I have actually had thoughts like, gosh, if I went to church every Sunday I would see my group of people,” Nowell-Smith said.

Wine is centered at this specific nexus of social connection (or lack thereof), environmental awareness and shifting views of alcohol. The new perspective that Millenials and Gen Zers bring to this aspect of the local economy provides a unique look at the changing social values in America, both as a marker of cultural or interpersonal isolation and engines for change.

After all, in vino veritas. In wine there is truth.

Most wine people are awash in the romance and poetry of their trade: winemakers wax philosophical about the magic of making a drink out of a living plant, growers rhapsodize about the hyper specificity of various strains, and collectors point to the subtle regional variations that round out their collections.

The process is part of the point, and that process takes time to unfold.

“Wines have a much longer view, right? If you’re making, let’s say Cabernet, that requires 20 months in barrel, that’s two years before you get to make money on it,” said Bryan Avila, associate faculty for wine studies at Santa Rosa Junior College and tech writer for Wine Business Monthly.

This longer view, however, is taking its toll as older generations age out of heavy wine consumption and minute-by-minute political maneuverings threaten small wineries who are unable to quickly react or adjust course.

The baby boomers have always had a healthy relationship with wine as consumers, said Amy Tesconi, an SRJC instructor who teaches wine club creation, maintenance, and promotion. Now they are simply starting to drink less wine as they get older, or begin drawing from their cellars or collections instead of buying new wine they may not have a chance to drink.

“There’s a lot of conversation around whether younger generations are drinking wine in the same way that older generations did,” Tesconi said. “The issues that I probably focus the most on are how these consumer attitudes are changing.”

And then there are the rising costs and tariffs associated with winemaking, further hampering the industry’s farsighted approach.

“It’s harder for smaller wineries to stay alive with rising costs of everything. You know, everything’s kind of gotten more expensive,” said Chris Christensen, associate faculty for agriculture and natural resources at SRJC.

Nonetheless, to many winemakers, the question is not how wine is going to survive: it’s how the shifting perceptions of the younger generation are going to impact it, and what that means about the state of society as a whole.

“Alcohol has been around since, what, 9000 years ago, 3000 years after the Ice Age?” Avila said. “People quit the hunter gatherer stuff, and started to dig into agriculture. Wine’s not going away.”

From yearly fire seasons to social media leading to heightened awareness for social justice and equity issues, Avila said the outlook of the younger generation is indelibly altering the industry, if for no other reason than the pure glut of influences vying for their attention.

“We know that the wine industry fluctuates every 20 to 30 years, which is about the time that you have generations, right? That’s the generational gap. And so really, every 20 to 30 years, you’ve got this market correction,” Avila said. “And so at some point, you’ve got to start to take a look at millennial and Gen Z values. What do they want?”

For a generation with apparently unparalleled acceptance and social license to act at they please, studies show a certain Puritan — or perhaps cautious — streak in young adults; younger millennials and Gen Zers are going on fewer dates, having less sex and — drinking less alcohol.

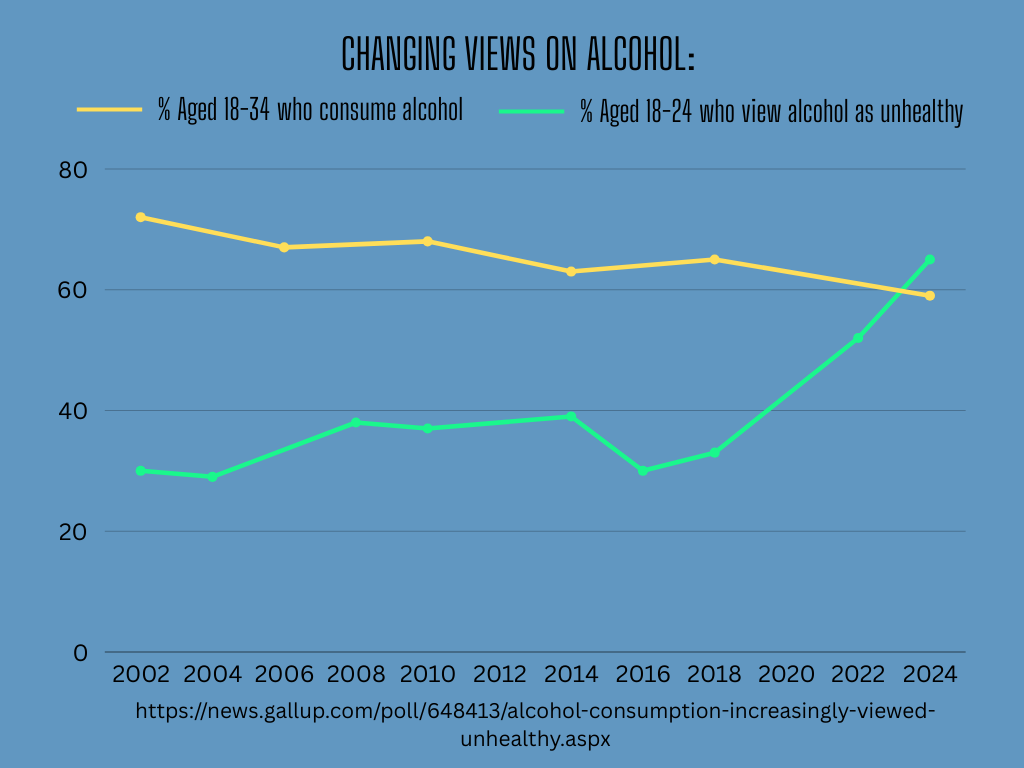

Young adults aged 18 to 34 are the largest U.S. cohort to express concerns about alcohol consumption and to say that their drinking habits have dropped significantly in recent years.

“Whereas 65% of U.S. adults aged 18 to 34 say alcohol consumption negatively affects one’s health, 37% of those aged 35 to 54 and 39% of those aged 55 and older agree,” according to a 2024 Gallup study.

The role that increased marajuana use plays in this question is also pertinent, but the direct relationship between people smoking weed and drinking less wine as an indicator of social values is more difficult to define than it initially appears.

More Americans smoke marijuana on a daily basis than those who drink alcohol every day, and those who do drink are more likely to express health concerns about their habit. However, marajuana has never had the same mainstream status as a cultural symbol of connection and business.

It’s not just that the youth aren’t getting drunk because they can get high instead, Nowell-Smith said, it’s that both trends show a shift away from communal inebriation.

“Definitely watching my parents made me not want to drink that much,” said SRJC student Kryssia Blandino, 19. “My dad drinks a lot and my stepmom smokes a lot, and I just don’t want to be around that.”

SRJC student Hevan Smith, 18, is studying to become a dental hygienist. “I’ve drank before, but it just wasn’t doing it for me. You know, I feel stupid, I feel sick,” she said. “I just don’t like the way alcohol makes me feel.”

Alcohol is the perfect poison, but only for a while. Upon initial consumption, alcohol increases the body’s levels of dopamine and serotonin, alleviating stress by increasing pleasure and happiness. Once the body processes the alcohol and the increased “feel good hormones,” the brain tries to recalibrate itself, producing more stress hormones like cortisol, according to Brentwood Behavioral Healthcare.

This rapid switch on the cellular level can have drastic effects on one’s mood, causing increased levels of anxiety, restlessness or panic. And thus the vicious cycle continues.

“Alcohol gives me anxiety for the next couple of days. That’s why I don’t really drink,” said SRJC student Nick Mendez, 25.

Of course, the United States has always had a bizarre approach to alcohol: unlike the majority of southern European cultures, which have long histories of wine and alcohol consumption as social and cultural norm (French schools were serving wine to kids into the 1950s), American kids end up drinking covertly until the ripe old age of 21, when the law says they can figure things out on their own.

“I’m paranoid of what could happen if I don’t wait,” said SRJC student Savanna Conwell, 18.

Young people have always looked for the best bang for their buck when it comes to alcohol: cheap beer and hard booze have always been — and will remain — the most popular vehicles for a buzz.

But there is also a prevalent pessimism and lack of social connection that winemakers like Kate Nowell-Smith point to when trying to explain why older young adults haven’t started drinking wine as they age out of partying.

“People want connection, but we don’t have it,” Nowell-Smith said. “Social media has destroyed connection and community. People are prioritizing getting likes from strangers over having a face-to-face conversation, and that’s terrible. Watching Netflix and getting high alone or playing a video game online with someone around the world is not at all the same as cooking a meal with them, eating food and drinking wine.”

SRJC business student Kenan Habt, 20, echoed that sentiment. She does not drink or smoke, but spoke about the way she – and many of her peers – see the world.

“It’s not looking too great,” Habt said. “There’s a bunch of concerns. There’s no one bigger than the other. It’s just all worry.”

Nowell-Smith summed it up similarly: “Yeah, we’re cooked. It’s not looking great for us.”

For wine to maintain its economic heft, Nowell-Smith said, the industry and wine culture will have to focus on connection.

“It should be about bringing families and friends together. It should be about sitting at the table,” Nowell-Smith said.

Michael Traverso is the vice president of business management for Wilson Daniels, a high-end importer and wholesaler of wine from around the world who mostly sells to upscale restaurants and wine shops who cater to collectors.

The kinds of collectors who end up buying the wines he helps import tend to fixate on a style or category of wine, he said. They buy deep so that they can preserve a memory of that moment in time of that vintage and the style of the wine for years.

Traverso doesn’t see this “collector” segment of the wine market going away anytime soon, but the luxury and privilege associated with wine culture do present a barrier to more socially conscious generations.

The clichés and typecasting in the wine business run deep. Unlike hard seltzers, which have done an excellent job of marketing themselves across class and culture, wine still comes with stereotypes and expectations, Nowell-Smith said.

“There’s this idea that women drink Chardonnay, men drink red wine, and you have to be a banker to appreciate it,” she said.

Younger drinkers are splitting from the habits of their parents, both as a conscious act of nonconformity and as concepts like brand loyalty fade from the cultural zeitgeist.

“People will criticize Gen Z for not being loyal. Like maybe baby boomers fixated on one producer, and they would join the wine club and buy for years, but the new generation seems to be way more exploratory,” Traverso said.

Distinctive and innovative wines such as orange wines, alternative whites and chillable reds were unheard of 20 years ago but now are flooding the market, even becoming a meme in the wine community, explained Christensen.

Purely by the numbers, the wine industry in Sonoma County is still deeply impressive: employees in the business earn $3.2 billion in annual wages, producing an estimated retail value of $8 billion, while the wine tourism industry currently generates $1.2 billion each year, according to the Sonoma County Vintners Association.

As such, the impacts that growers and winemakers worldwide are bracing for due to shifting social values, such as an aversion to alcohol or issues like widespread pessimism and disconnection, have the potential to rock other aspects of life here in Sonoma County for the worse.

But some growers and industry professionals see signs of hope in the very values and mores they are having to adjust to.

“Sustainability is very much becoming part of the culture,” Traverso said. “As the industry matures and people are asking about what’s in their glass, it’s definitely sustainability that they’re wondering about.”

It helps that many wine making processes in Europe come from traditions that have a deep respect for the soil, the environment and the land, Traverso said.

Younger generations are the most concerned about climate and environmental issues, and if they end up pushing for more innovation and sustainable and regenerative practices in the wine industry it could have a positive impact on agriculture as a whole.

Wine studies instructor Avila is also keeping an eye on the coming changes to agriculture.

“A lot of people are like, oh, yeah, technology will save the day. And I’m like, maybe. Probably not. You know, biology is going to save the day,” he said. “That’s the kind of thing that makes my socks roll up and down.”

Who knows? It might be biology. It might be technology. It will definitely require a readjustment to the different views on alcohol that younger generations are bringing to the table. It will hopefully serve to rebuild some of this social disconnection.

It just may be that the kids aren’t drinking enough.