Congratulations Los Angeles. Your Dodgers finally made it back to the World Series after a 29-year hiatus from Major League Baseball’s fall classic.

The same Dodgers franchise that jettisoned their Brooklyn home in 1957 in favor of La La Land; enticed by the glitz, the glamour and the promise of increased revenues. Never mind the fact that the team forcibly uprooted an entire pre-existing community in the process. So, again, congratulations Los Angeles. Your Dodgers, baseball’s equivalent of the original gentrifiers, reached the sport’s highest pinnacle.

The Dodgers have become so synonymous with the city of Los Angeles that it’s hard to remember a time in Los Angeles pre-dodgers. L.A. is home to one of the highest populations of Mexican-Americans in the U.S., which is naturally reflected in the team’s fanbase. Growing up as a Mexican-American in Southern California, you often find yourself walking a cultural tightrope. You’re either a “real Mexican” or a “Pocho,” a slang term for someone who is too Americanized and is no longer considered “a real Mexican.”

One of the barometers often employed when gauging how “Mexican” you are is whether or not you are loyal to the Dodger blue. The team has amassed an overwhelming amount of loyal Mexican-American fans, who have made it somewhat of a rite of passage in the culture. You’re not really “Mexican” if you’re a not a Dodger fan.

Being a Dodger fan doesn’t make you more of Mexican than a Mexican who isn’t a Dodger fan. Simply being Mexican makes you Mexican. It’s not a competition. There is no need to advertise your ethnicity to the world on a daily basis, there’s nothing to prove, no one’s handing out trophies. There’s nothing to gain from making someone of the same ethnicity feel inferior because of a misguided social construct.

Appreciate your culture but know your history.

And that’s where the irony comes into play. The Dodgers boast what is perhaps the largest Mexican-American fan base in all of baseball, yet the Dodgers are the one team in the history of the sport that has disrespected the Mexican-American community more than any other team.

To understand the level of damage the Dodgers franchise has inflicted upon the Mexican-American community we must go back, way back, to a time when the Dodgers were yet to exist in Los Angeles and a time when the Red Scare infiltrated every nook and cranny of society: the year 1957.

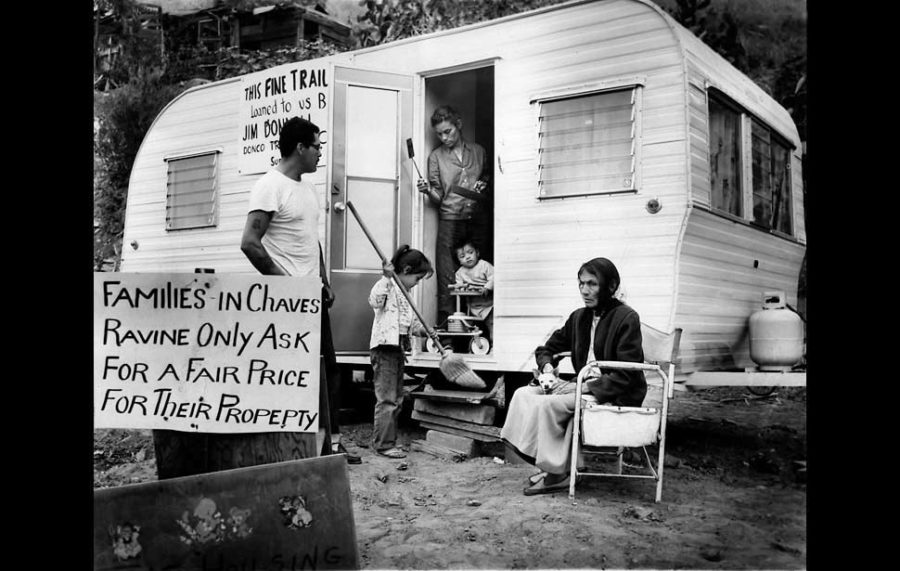

Chavez Ravine in Los Angeles in the 1950s was home to a rural community of Mexican-Americans who called those hills in Los Angeles home ever since fleeing the Mexican Revolution in the early 1900s. Mexicans built homes by hand from the ground up, raised families, grew vegetables and tended to animals in those hills. That all stopped when the Dodgers decided to move to town.

Walter O’Malley, the franchise’s hall of fame owner, grew unhappy with the team’s stadium in Brooklyn and like most owners today, threatened to move the team to a new city if a state-of-the art facility was not provided. Brooklyn couldn’t provide O’Malley with the new digs; enter Los Angeles stage left.

Los Angeles was eager to house a professional team to boost the city’s image as a cosmopolitan wonderland on the rise. The city also wanted nothing to do with an affordable, low-income housing project to be built for the large population of Mexican-Americans who settled in the hills of Chavez Ravine. Affordable housing sounded too much like some socialist-communist plot threatening to undermine the capitalist values that made America great in the atomic age.

So, the city of Los Angeles said “out with the Mexicans” and “in with the Dodgers.” Mexican-Americans who had been Los Angeles citizens for more than 50 years were forced to sell the homes they built by hand to the city for pennies on the dollar. Those who refused to sell were forcibly removed from their homes. When every Chavez Ravine barrio resident was finally removed, the city bulldozed the neighborhood to the ground, leaving nothing but a wide open parcel of land, an ideal setting for the construction of a state-of-the-art baseball facility.

From that moment on, the city of Los Angeles has been the proud home of the Dodgers. A team that has profited off the Mexican-American community by exploiting them for decades. Sure, when Fernando Valenzuela burst on the scene, the Mexican-American community in Los Angeles began to forgive, but we should never forget.

I understand it happened more than six decades ago and that my hatred may run a little too deep, but those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it. We must learn from this and ensure that it never happens to another community again.

When the World Series begins this year, I’m not rooting for the Dodgers. I’m rooting for the team that didn’t uproot an entire community of Mexican-Americans. I’m rooting for the Houston Astros, a team with the power to uplift an entire community still reeling from the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. I’m also not rooting for the Dodgers because I happen to be an Angels fan, but that’s an entirely different story.

If you are interested to learn more about the history of the Dodgers and Chavez Ravine, read “Shameful Victory: The Los Angeles Dodgers, the Red Scare, and the hidden history of Chavez Ravine” by John H. M. Laslett.

ALeyva • Oct 25, 2017 at 12:10 am

My father is 90 and was born and raised in Palo Verde, Chavez Ravine. I’m looking to get him interviewed for family documentation purposes if you’re interested. He’s a die hard Angel fan!

michael barnes • Nov 3, 2017 at 10:20 am

@ALeyva that is awesome. I would definitely be interested in interviewing your father.