Believe it or not, Robert Ripley rests just minutes away from the Santa Rosa Junior College campus, and his grave at Odd Fellows Cemetery is even marked with his catchphrase.

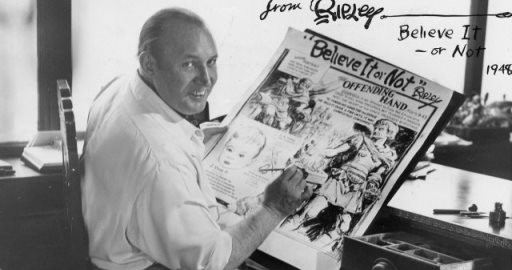

By the peak of Ripley’s career in 1933, 60 million people read his daily “Believe It or Not” cartoons, published in 300 American papers and in nearly 40 foreign countries.

He died in New York City on May 27, 1949, but his body was railed back to the city where he was born and raised: Santa Rosa.

The front page headline for the Saturday, May 28, 1949 issue of the Press Democrat (P.D.) read, “‘BELIEVE IT OR NOT’ RIPLEY DIES; SANTA ROSAN TO BE BURIED HERE.”

Press Democrat reporters Mike Pardee and Robert Boardman gathered anecdotes from Ripley’s family and friends for an extensive obituary the day after his fatal heart attack.

Despite a few factual discrepancies, the message was clear: Ripley was a talented man who never forgot his roots, even after his fame and success had offered him the world.

Emerging Talent

Ripley developed an inferiority complex at a young age due to his protruding front teeth, which contributed to his sensitive and shy disposition.

His schoolmates, however, remember him differently in the P.D. obituaries.

“He was just a real kid, one of those kids everyone liked,” William Corrick said.

Ripley got his lifelong nickname, “Rip,” during his time at Santa Rosa High School where his studies came last.

“He wanted to be a professional baseball player, and for a while earned $6 a game as shortstop on the Santa Rosa baseball team,” said Mrs. Neil Griffith Wilson, a close friend.

Former SRHS athletic manager George Proctor said, “Rip was head and shoulders above any high school pitcher in Northern California.”

Larry Walker, captain of the SRHS baseball team in 1906, even claimed that Ripley was a better baseball player than artist.

Fortunately for the future entrepreneur Ripley’s English teacher, Frances O’Meara, recognized his artistic talent.

Ripley submitted his illustrations of the characters in Tennyson’s poem, “Idylls of the King,” instead of the written review assigned in class; O’Meara, impressed by the accuracy of his drawings, allowed him to continue.

He eventually illustrated every work of English literature taught by O’Meara.

Ripley also drew hundreds of sketches for the SRHS student newspaper and yearbook, all destroyed in a 1921 fire.

“I cannot help but feel that a part of me was destroyed in that fire. Their loss can never be replaced,” O’Meara told Ripley.

Ripley dropped out of school in the spring of 1908 to support his widowed mother and accepted an offer from the San Francisco Bulletin to work as an illustrator for $8 a week.

“The Bulletin looked over [Ripley’s] cartoons and offered the 16-year-old Santa Rosan a job,” Pardee wrote.

And so his career as a cartoonist began.

Famed Phrase

Ripley revealed the inspiration behind his catchphrase, “Believe It or Not,” in the Dec. 19, 1938 issue of the New York Daily Mirror.

“Twenty years ago today, I was sitting before a drawing board… I found myself at a loss for an idea,” he wrote. “The deadline for the next day’s paper was fast approaching.”

He turned the few athletic oddities on his desk into a cartoon and hastily captioned them “Believe It or Not.”

“I sent this make-shift drawing down to the engravers and went home, thinking I had done a very bad day’s work,” he wrote.

To Ripley’s surprise, his editor asked him to turn his idea into a weekly cartoon, and the rest is history.

“The phrase he so happily hit upon has become an integral part of the English language, and probably will be repeated as long as the language is spoken,” the P.D. wrote.

Coming Home

When he heard his former teacher O’Meara’s plans to stop in New York en route to Europe, Ripley greeted her with a limousine ride and a suite in her name at the Waldorf-Astoria.

“He was like that,” Wilson said. “No matter how rich or well-known he became, he still kept in touch with his old friends.”

Ripley personally inscribed his books and cartoons to his old friends.

“We had a class reunion, but he couldn’t come. He sent a telegram and the books instead,” schoolmate Eliza Tanner said. “I still have mine.”

After completing a world tour in 1932, Ripley returned to the SRHS auditorium to speak at a reception that drew over 1000 people.

“He was very grateful to all who helped him make a success of his life,” schoolmate Harriet Barnes said.

Local Legacy

Ripley’s 1949 obituary revealed that he had proposed to “go 50-50” with the city in buying and renovating the Baptist Church, but City Manager Ed Bloom declined due to its high estimated cost.

“He felt pretty bad about not being able to make a memorial of it for his curios and decided to give up the idea when the city wouldn’t cooperate,” Ripley’s sister, Ethel, said.

His wish was granted in 1970 when the Church of One Tree— where his mother had attended services— became the Ripley Memorial Museum.

Incidentally, his father had also helped build the church in 1873 from a single Guerneville redwood tree, 275 feet high and 18 feet in diameter.

The Church of One Tree, itself a curiosity, was “stocked with curiosities and ‘Believe it or Not!’ memorabilia’ for nearly two decades” and renovated in 2009, according to the City of Santa Rosa website.

Ripley discovered thousands of oddities for us to believe, but it was his friends and family that made us believe in the man himself.

“He was one of the finest kids I ever knew,” Corrick said.